COVID vaccines: From me to we

An understanding of our social selves is needed to tackle vaccine hesitancy

Vaccination is an inherently social activity – we vaccinate not only to protect ourselves but also to protect others. This creates particular challenges as for many people, they may choose for themselves to not get vaccinated as the personal risk to them if they catch COVID-19 is low. But their actions have implications for other, more vulnerable members of the population that can then be at greater risk because of their decision.

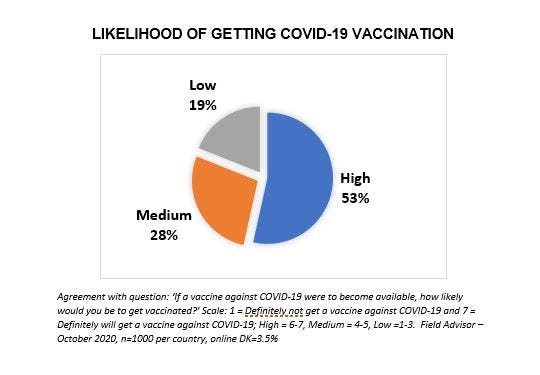

We undertook survey work in October 2020 that was used to inform later polling for the World Economic Forum. It’s worth revisiting some of the original analysis as we had a very rich behavioural science insights from the data. At that time half the population in the countries we interviewed considered they were either of low or medium likelihood to be vaccinated, this is of real concern.

It is the very social nature of vaccination – in the protection it provides to others – that means we need to use this lens to explore what can be done to address COVID-19 vaccination. There is much evidence that in many contexts, people are motivated, on the whole, to act for the good of their wider communities. Indeed, throughout much of 2020, the vast majority of the population has complied with governments’ public health guidelines, despite their personal risk of adverse impact of COVID-19 being low.

If we can generate a sense of ‘we-ness’ as Professor Stephen Reicher calls it, then we operate not simply out of self-interest but also thinking of other people that we care about. The task to be done is to encourage ‘we-thinking’ so people are more likely to operate in terms of communal rather than individual interest. And we firmly need people to operate for the good of the community as the majority could catch COVID-19 and recover without major loss.

But just how do we make decisions that lead us to think of our own personal risk versus the wider community? The answer lies in the very issue we are trying to resolve. There is a growing body of evidence that much our decision making is strongly socially influenced by the communities and culture we are part of. Perhaps this is no surprise as humans are a social species, we are not just reliant on ourselves for knowledge and well-being but each other. Our reliance on others necessarily means that beliefs do not exist in a vacuum but have a significant social element to them. Some groups of the population may identify themselves with a set of values that are highly individualistic whilst others may have a more communitarian outlook. Despite that, the mechanisms that shape these beliefs are still inherently social in nature.

Which means these beliefs are also intertwined with shared cultural values, our identities as well as other related beliefs. If we are going to discard a belief then this is a not a simple reorganisation of the way we see the world but means we have to also discard other beliefs, turn our back on our communities, set ourselves against people close to us, and fundamentally start to rethink our identities.

We need to leverage the all important social mechanisms that shape our beliefs in order to encourage a ‘we-ness’ in outlook with regard to COVID. We argue for addressing the challenges with a social lens – both in terms of encouraging a collective outlook but also through an understanding of the way in which our beliefs, attitudes and behaviours are very much shaped by the communities we are part of.

Set out below are the ways this plays out across some of the key themes that emerge from our survey work on COVID-19 vaccine take-up:

Support trust in information sources: Those with low likelihood to take up COVID vaccination are much less likely to trust information sources, with 59% of people overall saying they would need to think hard about getting a vaccine. Public health bodies and other institutions need to understand how they can align in a way that is part of their community of understanding and builds trust, creating an environment to support critical thinking

Build social norms to counter anxiety: Across all groups, regardless of likelihood of getting vaccinated, 53% of people are anxious, which can quickly translate into further hesitancy. An effective way to manage this anxiety is facilitate seeing other people that are known and trusted get vaccinated: building strong social norms around vaccination can help manage this effectively.

Build positive social identities: With 77% of people considering that vaccination is their personal choice – it is important to weave this sense of autonomy into part of a wider pro-social identity where it is recognised that they have a choice but their identity as a member of a wider community means they choose to take this up

Encourage vaccines as normal health protection routine: Vaccination is no longer a normal part of health protection routines for many, with only 40% of people being vaccinated for the flu last year. Demonstrating the way in which many other people in their communities they value make this a normal part of what is done is critical to help form and maintain positive outcomes.

Too often appeals are made to individuals to change or adopt behaviours on the assumption that we are creatures that only operate according to our individual self-interest. But there is a growing body of evidence that what matters to people is their memberships of communities that they value — and which then defines their sense of self. We need to nurture people’s sense of memberships groups that value the consideration of the consequences not just to oneself but to others.

Behavioural scientists have long been aware of these mechanisms but too often choose to focus on individual rather than group decision making. This is the point at which we know need to refocus the discipline and broaden its perspective, using the huge body of work and experience to support the social mechanisms to deliver a sense of community and collective consideration of the consequences for all.