Moonshot Mindset: The need for big thinking & New Behavioural Science

2023 looks set to herald in an era of 'New Behavioural Science' as recognition of the way societal ecosystems shape behaviour moves centre stage

One of the revelations of 2022 was the paper stating there is ‘No evidence for nudging,’ marking the point at which the focus on the individual as the primary agent for change finally charged course. This presents a challenge to a world in which individual action is held to be the core means to create positive outcomes: as we have pointed out previously, the notion that we are all individually responsible for our ability to act on and shape the world is widely considered the reason for our collective successes and failures.

The problem, as Mariana Mazzucato, author of Mission Economy points out, is that after a long period of this individualistic approach, “not much is changing.” She argues that our current systems have failed to make change happen on a number of fronts. She suggests that rather than having a sustainable growth path, we have instead ‘built economies that inflated speculative bubbles, enriched the already immensely wealthy 1 per cent and are destroying the planet.”

But surely we can vote with our feet our our wallets? No so suggest, writer and activist Cory Doctrow and academic Rebecca Giblin who make the point that that when markets are working and there is plenty of competition, then our individual choices can indeed make a very real difference. But in the situation that they argue we find can often ourselves in today, there is often little effective choice, in which case ‘you literally cannot decide to go elsewhere while still participating in our …society.’

So 2022 was the year where it started to dawn on us that individuals are a necessary part of change but far from sufficient. Instead, people such as Mazzucato, Doctrow and Giblin suggest that if we want to change the world, we have to fix the system. Which means we need social and political solutions – and the most important individual action any of us can do is to join a movement where we are connected with others to make wider change happen.

The Mission Movement

The focus then for change to happen is increasingly understood not to be solely the individual but instead we need a wider rethinking of the macro aspects of how we structure our economy, to reflect a more symbiotic and mutualistic ecosystem. Clearly this is no small feat: indeed, Mazzucato argues this requires the same level of boldness and experimentation of the 1960s Moonshot programme, the ambition of landing humans on the moon. This programme involved a fundamental rethink of the economy and society, and above all a sense of public purpose which Mazzucato says is needed today.

Mazzucato’s prescription to deliver this is for governments, in dialogue with citizens, to define the big challenges of our times and to set missions to solve them in partnership with business. These missions should be bold and inspirational – from solving the climate crisis to curing cancer to eliminating the digital divide. By focusing on the ends rather than the means, policymakers can create the space for creativity, experimentation and collaboration across sectors, reflecting how the most important problems today are collective action problems rather than individual behaviour change ones.

To achieve this she argues:

“A renewed sense of purpose must go to the centre of the relationship between organisations in the economy…change comes from reimagining how different organisations and actors in the economy co-create value.”

With this, we move from notions of ‘redistribution’, and instead figure out ‘predistribution’, thinking how to create a more symbiotic structured way for economic actors to relate, collaborate and share.

Mazzucato’s Mission Economy puts government in a mediating role at the heart of this whilst a related movement, the ‘Economics of Mutuality’ focuses on businesses as being central. This suggests that relationships within a corporation, their suppliers, consumers and society, should recognise, sustain and grow the benefits to each party.

Mutuality is defined as the creation of shared and lasting positive benefits across stakeholders through an organisation's activities and through this become stronger and more sustainable.

Both argue for the same degree of boldness and sense of purpose but played out primarily by the wat we organise ourselves societally.

From choice architecture to choice infrastructure

These big thinkers are making a potent case for the way we have for too long relied on individual level solutions and how our focus needs to shift. 2022 has also seen this view permeating into the behavioural science landscape with Nick Chater and George Lowenstein calling for us to move from a focus on the ‘I-Frame’ (individual level solutions) to the S-Frame (systemic reforms) is now moving centre stage. And in terms of practitioners working in this field, Ruth Schmidt makes the case that the challenges we face are simply too complex for traditional ‘nudge’ solutions that have been in favour for the past few years. Instead, she argues:

“Solutions within complex systems must look beyond tweaks to immediate choice architecture environments and instead address the ways in which broader system conditions contribute to individuals’ abilities to choose and maintain preferred behaviours.”

One example she gives is the way that early approaches to boost COVID vaccine uptake focused on nudge style message framing to overcome vaccine hesitancy but in doing so overlooked the fact that concerns about taking time off to receive the vaccine and manage potential side effects which in fact were much greater deterrents for some segments of the population.

Tools for change

The challenge is that to actually do something, practitioners need tools for applying this wider ‘systems’ approach to make change happen. There is no shortage of tools to facilitate a rigorous means of systematically assessing, implementing and supporting individual behaviours: now the same is needed for the development of infrastructural conditions in order to shape positive outcomes. And while there are change management models, as Schmidt points out, these all too often focus on abstract processes and generalised attributes rather than setting out in very practical terms how to encourage new behaviours.

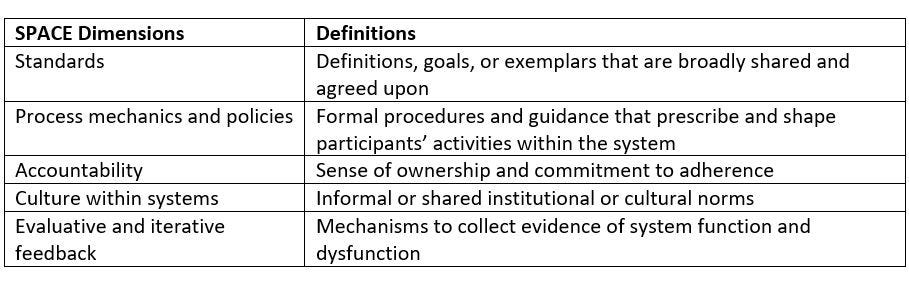

Of course some behavioural science frameworks have this as part of their model (for example the ‘O’ in COM-B or the outer layers of ISM) but perhaps not with the level of detail that it is becoming clear this issue deserves. Schmidt proposes a SPACE model, the summary of dimensions and definitions of this are shown below:

To explore this further, do read the paper: we suspect that while this is a helpful tool in its own right, practitioners will also use this as inspiration for their own versions to fit with their practice needs and preferences.

What this looks like

One example of applying this type of approach is Novo Nordisk, that has a core purpose of driving change to defeat diabetes and other chronic diseases. While their philosophy and business model has been to discover, develop, and manufacture medicines to tackle diabetes, the firm recognizes that it takes more than medicine for people to live a full and healthy life with diabetes.

In 2014, the company launched the sort of ‘Moonshot’ the Mazzucato suggests is needed. Cities Changing Diabetes was their response to the ‘unsustainable global rise of type 2 diabetes’. This created a public–private partnership focused on bringing different stakeholders and expertise together to find infrastructural solutions to address the rise of diabetes in urban areas.

A review found that the majority of the actions by this work, initiated concern community involvement in health, health-promoting policy, and health-system strengthening – indicating just the sort of ‘choice infrastructure’ changes that Schmidt (and the Economics of Mutuality) is suggesting are needed for change to happen.

In conclusion

There are many implications here for behavioural scientists as we enter 2023 where the tough problems we are facing are no longer managed solely by individual-level sticking plasters. This is an exciting moment and the provision of practitioner tools, as offered through SPACE is an important as the conceptual shift that has been underway for a while, is now translating into tangible changes in the way practitioners are working.

This has knock-on effects with, for example, testing and evaluation given that RCT’s and field experiments are not always well equipped to deal with complex conditions and multiple variables that are tackled in infrastructural changes. There is also a pressing need to address the mindsets of organisational decision makers so they can better understand the limitations of the way they can at times frame the issue overly individualistically.

Traditional behavioural science clearly continues to have a role to play albeit the evidence base clearly indicates we need to avoid over-reliance on individualistic solutions. 2023 looks set to see a paradigm shift towards a new formulation of the discipline - New Behavioural Science’ we might call it.

Here at Frontline Be Sci we will continue to cover these changes and push the boundaries of the discipline in a quest to help us make sense of, and find more effective solutions for, the big challenges we are facing in the world today.