The ghostly memories shaping our lives

How eerie feelings of the supernatural gives clues to how the mind works

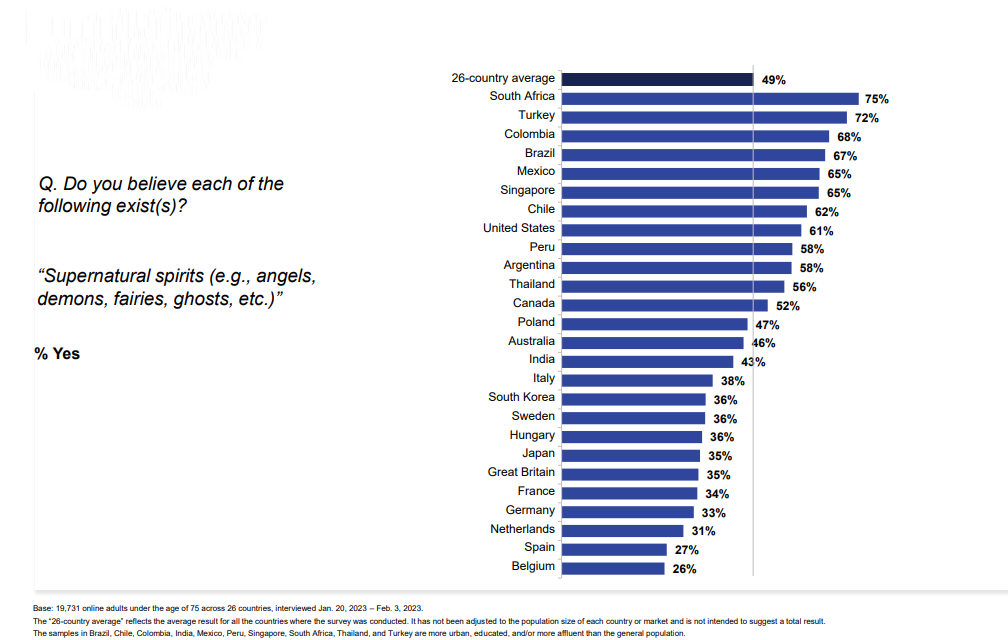

With Halloween upon us, now is a good time to share the interesting finding that about half the world’s population believe in ‘supernatural spirits’ – a term that includes angel, demons, fairness and ghosts. For a world where rational scientific understanding is often taken for granted, this number may seem surprising to many.

Of course, supernatural spirits do exist for many people– and we are not challenging people’s beliefs about this at all. But we do argue that the spooky experiences many of us have occasionally offer a compelling lens to understand humans and the way memory and cognition work.

Haunted by memory

Supernatural beliefs that involve ghosts will often draw on people and events from the past, intruding into the present. In some ways this is not a new idea, we can see all around us how history resides in our memories, passed down through generations, with resulting controversy and confrontation in the present. This is illustrated by a recent documentary on the history of the UK where interviews with people in Scotland at times found historic references shaped sides of the debate to Scottish devolution: the battle of Culloden in 1746 acts as a rallying point for Scottish nationalism, with those on the other side of the debate sometimes pointing to the economic benefits they saw from the 1707 Act of Union. So memories of the past clearly continue to shape the present in a very visceral way.

Another way in which the past has been considered to shape the present in perhaps more eerie ways is the concept of ‘hauntology’: coming from philosophy and cultural theory, it refers to the persistence of some elements from our past as if they are ghosts that haunt the present. The term, first coined by Jacques Derrida, uses the concept of the ghost as a metaphor to discuss the way the past ‘haunts’ contemporary thoughts. There is a particular focus on cultural references, such as outdated or obsolete technologies, styles, and genres, which continue to ‘haunt’ contemporary culture creating a sense of temporal dislocation. We can surely see this all around us in the nostalgia for past decades, the revival of vinyl records, or the influence of 1990s aesthetics on contemporary fashion and music, for example.

In this way the past is not something that is gone and finished. Instead our memory operates in a way such that some things linger in the present in unpredictable ways, disrupting our normal explanations of time as something linear.

The strange feeling of being out of time

The strange feelings of dislocated time that is referred to in hauntology might also be seen in the ghostly feeling of déjà vu, a French term that means ‘already seen’, referring to the strange sense that a new situation or experience has been encountered in the past. According to Anne Cleary, professor of psychology at Colorado State roughly two-thirds of us experience déjà vu at some point in our lives. She describes it as a process that occurs:

“…when there is a hiccup in the system, and we notice the pull on our attention; it grabs hold of our focus, allowing us to catch a quick glimpse of our memory’s operation occurring in slow motion.”

We could perhaps relate this to the way memories work so that barely remembered shared stories, myths, events can unexpectedly spark a feeling of déjà vu for something in the present. We might struggle to make the connections due to a weak individual or collective memory, but we get a sense of something there. As Clearly points out, in these instances intuitive processes are suddenly disrupted:

“What would ordinarily take place quickly beneath the surface…suddenly has a light shining on the spot where the halt occurred, where the retrieval piece was not successful, and we find ourselves in a heightened state of searching our memory, trying to find out why the situation feels so familiar.”

These phenomena may seem strange if we see memory in the way it is often described, as a form of information processing, encoding cues and associations that are accessed by tapping into a ‘memory bank’. But perhaps at this point of the year, as we can reflect on the way the past can intrude into the present in sometimes eerie ways, we can see that memory is more subtle, culturally shaped and simply more interesting than what a computer can offer.

In conclusion

While science is often considered purely objective and literal, it frequently draws on metaphors to help us to understand complex concepts, in this case memory as information processing. Of course, if we are not careful, these metaphors can start to disproportionally shape the way we see things, determining where research activities are directed, what papers are published and so on. Taking stock of human experiences such as those relating to ghostly experiences allows us to challenge the dominance of some metaphors and allowing us to consider some alternatives.

One possibility comes from philosopher Michel Serres who suggests that time is like a crumpled handkerchief. If you take a new folded handkerchief and spread it out, then you can see in it certain fixed distances and proximities. But if you take the same handkerchief and crumple it, then two distant points are then close. And if you then tear it, two points that were close can become very distant. He uses this to suggest that time does not flow but instead ‘percolates’. We can readily apply this to the way memory works, and how old ideas, theories, and arguments do not vanish but instead, remain undisturbed until collective events, shared experiences, moments of déjà vu mean they reappear at apparently unrelated moments to combine with newer arguments and narratives.

For years the notion of the iceberg for describing human behaviour arguably had a huge effect on the emerging discipline of behavioural science, something that is perhaps only recently being challenged. A healthy dialogue of the metaphors we use seems important and as such the ‘crumpled handkerchief’ metaphor for memory may be an interesting and useful starting way to better describe the experiences we have of the past and the different ways it intrudes into and shapes the present.