It seems we really do believe in magic

It seems impossible but when put under pressure, people do somehow seem to have a range of magical beliefs, telling us something important about human cognition

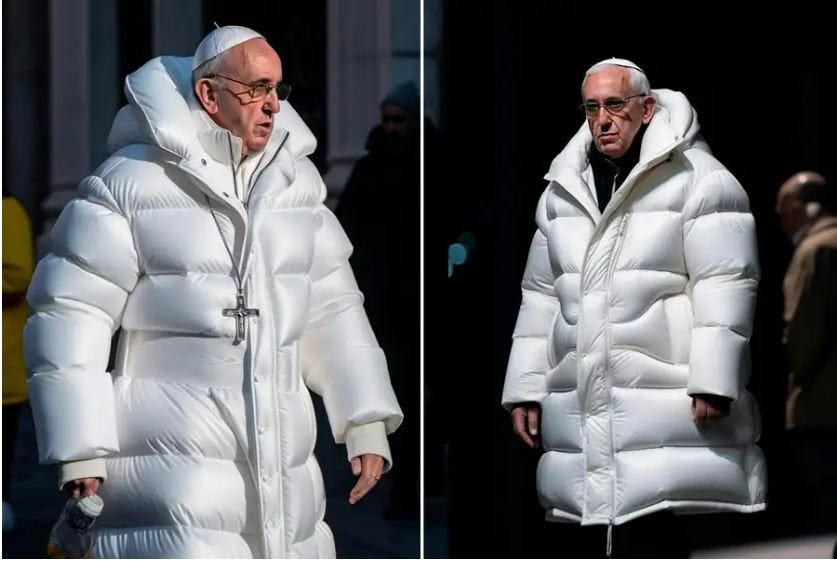

A widely shared meme earlier this year was that of the ‘Pope in a Puffer’, showing Pope Francis looking stylish in a silver puffer jacket. Just why did this create so much interest? Perhaps one clue to this comes from science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, who famously observed that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. It is clear that the notion of magic is something that fascinates us but why? We argue that is, in part at least, because although we rationally deny its existence, at some level we act as if it does.

In fact, there is in fact a great deal of psychology literature on way magical beliefs shape the way we engage with the world. Beliefs about the magical properties of items is important as it applies to a wide range of the ways we engage with the world having wider social, cultural and political significance.

The history of magic

In medieval times people considered magic was simply an element of everyday living, with it used as an attempt to influence something outside of the bounds of the natural world. People would combine words and actions to try and change or influence something in their lives that they couldn’t control through ordinary means. Examples of the everyday nature of magic from this period include the way people not only created an herbal remedy for an illness, but recited words and performed actions to draw supernatural forces to increase the potency of the medicine. Another use was for predicting the future: this included making use of what was considered magical information in the calls of birds or the paths that they took as they flew across the sky.

Whilst in medieval Europe, there was no particular distinction between magic and religion the Reformation, the transition from Catholicism to Protestantism arguably stripped Christianity of its magical power to provide believers protection from misfortune. This movement caused a decline in not only the use of magic, but the belief in magic as well. The scientific revolution maintained this momentum, albeit many of the principles of the methods of science were developed from magical origins (such as astrology).

Magic today

Given this context, we might expect magic to have firmly been consigned to a footnote in history, yet magical beliefs have persisted over time. If we look at more recent history we find evidence for widespread belief in magic. Historian Owen Davies sets out the way Oujia was hugely popular at one point, where a movable indicator is used and moved about a board to spell out words during a séance. Another area was spirit photography, a type of photography whose primary goal is to capture images of ghosts and other spiritual entities.

Psychologist and magician Gustav Kuhn points out that magical concepts continue to play a role in our adult lives. He suggests they help us deal with complex situations that we would otherwise simply fail to grasp, and they can make the inanimate world more fathomable. For example, every time we empty our computer’s trash folder, we accept the magical belief that the files have been deleted. This is a far more manageable a concept for us than having to deal with an intricate of computer programming explanation.

In another example, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder can be seen as “magical thinking” because it often involves supernatural associations of cause and effect. For example, an individual might have an intrusive thought: If I tread on cracks in the pavement, I will get into a car accident. They then alleviate the fear by performing a series of rituals and avoidance behaviour, driven by the perception that such rituals could ‘magically’ prevent the accident.

There has also been experimental evidence that suggests despite conscious disbelief in magic we continue to act as if it is true. In one study, participants were shown an apparently magical effect: a square plastic card became badly damaged in an empty box after a magic spell was cast on the box. Participants then tested using either a) a low-risk test condition where driver licences were at risk of destruction by a magic spell or b) a high-risk test condition where participants own hands were the object at risk of being damaged as a result of the spell.

Results showed that in the low-risk condition 12% of participants prohibited the magic spell, but in the high-risk condition 50% asked the experimenter not to use the spell and justified this by saying it might damage their hand. So placed under stress, it seems many of us do exhibit and do seem to reference beliefs about magic to be shaping our behaviour.

Misdirection

Long term scholar of beliefs in magic Eugene Subbotsky suggests that laws of science have a number of key principles that mean magical properties are not feasible and yet we maintain a degree of belief in them. The work of psychologists Paul Rozin and Bruce Hood suggest that we can indeed find evidence of these sorts of beliefs in the population, which tend to only appear in specific circumstances and yet might reveal something broader about our beliefs.

The laws of contagion

According to this magical law, things that once have been in contact with each other may influence each other through transfer of some of their properties. This influence remains after the physical contact has ceased and can be permanent. In traditional magical practices, contact is often through personal ‘residue’; a lock of hair, nail clipping or scrap of clothing for example are considered to retain some essential properties of their original owner. This means that action taken against the residue can affect impact the original source – for example, in traditional practices voodoo dolls will often incorporate hair or clothing from the victim.

Of course, scientific laws would set out the way different objects are independent of each other and would not have any linkages and we might therefore expect to see any evidence of this residing in peoples beliefs.

To examine this, we can turn to Bruce Hood who, in a famous experiment, offered people a financial incentive to wear a second-hand but cleaned and disinfected cardigan. Understandably, most people agreed to wear the item. But then he asked, ‘Would you still wear it if you knew it belonged to Fred West?’ (a notorious mass murderer.) Most people then refused saying it felt disgusting or dirty. So we can see the notion of contagion does in fact seem to be activated here – somehow the cardigan had taken on some properties of its previous owner and as such we did not want to be contaminated by it either.

In another example, Peter Ayton and colleagues examined the effect on property prices of London’s blue plaques, commemorative plaques that are erected on buildings to serve as historical markers of notable men and women who lived in them. They found that after a plaque is installed, the sales prices of London properties increased by 27% more than the sales prices of other neighbouring properties over the same period.

The Law of similarity

A second law, ‘similarity’, suggests things that resemble one another share fundamental properties. As with contagion, the image is believed to contain the essence of its ‘source,’ so that action on the image can produce similar effects on the source. Hence, when two objects that resemble each other, at some level we can assume they are connected.

One example of this is herbalism, where medieval books such as "The Doctrine of Signatures", suggest that the appearance of a plant hinted what it was useful for. On this basis, it was suggested that figs treated impotence and infertility because they vaguely resemble testicles and ginseng was a considered a potent treatment for blood disorders because it looks like veins.

To examine the degree to which this might hold today for a wider population we can again turn to Paul Rozin who asked people to do a range of behaviours such as drink soup from a brand new, pristine bedpan or eat chocolate that looked like dog turds. Despite the participants being raised in a rationalist culture and knew items were safe to consume, most showed a marked preference for eat or drinking from an alternative source.

A more recent example of this is the outcry that the company Boston Dynamics received about a video posted online showing employees trying to kick robotic dog, Spot, over in order to show how robust it is. The video spread like wildfire and raised huge questions in the media about the ethics of how we treat robots. It seems that the fact we are asking this question suggests the magical law of similarity is still present in our beliefs.

Magic and digital design

More than two decades ago, usability consultant and designer Bruce Tognazzini made a case for applying stage magic principles to human-computer interaction. He observed an "eerie correspondence" between the two fields and encouraged a broad array of researchers and designers to probe and use ideas and techniques from magic in interaction design (see this paper for a great review of this area).

And in fact much of the work on the psychology of magic (such as this paper) has tended to focus on the way in which magicians are expert in manipulating people’s perceptual experiences. The scientific study of misdirection and deception explores the way in which our attention is diverted often involving a wide range of cognitive mechanisms. Gaming design is another area of focus which is not surprising given it also shares similarities with magic; games are often set in fantastical worlds where magic is real and both game designers and magicians strive to create an engaging experience for their audience, seeking to create engagement and surprise.

In conclusion

For our purposes, we are less interested in the craft of the stage magician to give the appearance of magic and more interested in the beliefs we have that reflect an assumption that the world works according to magical principles. The research of people such as Paul Rozin suggests that we do in fact, at some level, have a belief the world works this way although we deny it when asked.

A useful term here was coined by philosopher Tanar Gendler: ‘alief’, the notion of the unexamined, intuitive beliefs we hold that are automatically released in specific circumstances (such as the fear that we suddenly experience when walking over an abyss on a safe but transparent bridge).

The finding that we continue have magical ‘aliefs’ suggests we have fertile imaginations that can break free of consensus thinking, and that even the most widely accepted principles of the way we understand the world can be debated and challenged. Returning to the ‘Pope in a Puffer’, arguably our fascination with this reflects our ‘aliefs’ how we enjoy playing with magical concepts and possibilities.

Rather than seeing our intuitive belief in magic as a weakness in humans or a sign of our tendency towards grabbing comforting easy answers at times of stress, perhaps we can instead see this as an indication of human creativity and our collective willingness to imagine the impossible. And in the environment we live in today, many might consider this to be an asset rather than a deficit.