Just what does come naturally in the food we eat?

The psychology of naturalness is at the heart of a debate about plant-based food

There has been an explosion in plant based foods with a recent report finding that 48% of the UK adult population claim to include at least one type of plant-based alternative to cow’s milk in their everyday diet (and 58% include at least one type of plant-based meat alternative). The finding is impressive for the industry, which is seeing record levels of investment.

The growth in the market is also a source of some controversy, with a recent report by Bloomberg suggesting that ‘plant-based meat is turning out to be a flop’. The article, was criticised by leading plant based food manufacturer, Impossible Foods, who called it “one-sided anecdotes and editorialized framing.” No doubt this debate will continue to run but it does raise the question of the degree to which demand for plant based foods will match the investment.

To maintain the growth we have seen, it will be important to understand the different barriers to purchase of these types of food. And a key consideration was recently flagged by Unilever in their quest for ‘cow-free’ ice cream. Their R&D centre is exploring the use of ‘precision fermentation’, essentially using yeast to make dairy proteins (such as whey) that deliver the flavour of animal milk. The challenge posed by Unilever President of Ice Cream Matt Close was that customers may not perceive products made this way as being ‘natural.’ He suggested “What you don’t want consumers to think is that this is somehow fake and too scientific.”

This is certainly backed up by polling data (from the US at least) that indicates people have much greater trust in ‘foods that are naturally occurring,’ as shown below:

At one level, the evidence seems clear, that naturalness will win the day, and this could represent a challenge to the potential of plant-based foods. But if we take a closer look then the findings are perhaps less clear. For example, while there is some resistance by meat eaters to become ‘flexitarians’ due to concerns about the ‘naturalness’ of plant-based milk and meat (see below), whilst there are also a similar number (10% for meats and 13% for milks) that feel that plant-based options are the more natural (data drawn from this report).

So just what foods we consider to be natural is clearly contested: perhaps to understand how to address this, we need to better understand the underlying psychology of the way we think about naturalness.

Defining natural

What does ‘natural’ mean to you? Is it a physical property of an item that has been freshly picked, for example, or home grown? Or is it something more abstract or conceptual? Either way, naturalness is desirable; it evokes images of untouched wilderness and of freedom, and can conjure a sense of spirituality, imagination or potential.

Equally important is the feeling that naturalness carries a sense of appropriate order, or rightness - things are operating as intended. The word ‘natural’ in consumer marketing, especially in food, conveys ideas of purity, healthfulness and, above all, value. Consumers, regardless of age, gender or other demographics, seem to consider ‘natural’ foods more desirable and worth more than ‘non-natural’, ‘artificial’ or ‘processed’ alternatives.

There are typically two types of justification for wanting naturalness: instrumental and ideational. Instrumental reasons, which are the focus of much research, refer to the perceived advantages of naturalness, the feeling that it is inherently better - more attractive, healthier or kinder to the environment. But it is not as simple as this. When consumers’ instrumental reasons for preferring a natural item have been neutralised by offering, for example, an option that is chemically identical, the preference for the naturally derived item remains.

This suggests that we also have ideational notions of naturalness – more abstract moral or aesthetic concepts, as opposed to the material health or environmental benefits of instrumental justification.

An example of how this ideational conception of naturalness can matter as much, if not more, than instrumental reasons is the ‘toilet-to-tap’ phenomenon. All water is physically contaminated, and endlessly recycled. However, when people are asked if they would drink water that has been recycled from toilet water, the vast majority of consumers refuse to do so. The idea evokes feelings of disgust, a strong emotion often associated with bodily products. There are no practical (instrumental) reasons why we should not drink this water: our concern is to do with how we think and feel about it (our ideational response.)

Naturalness and processing

So what determines these ideational properties? One key finding from psychology suggests that our perceptions of naturalness of foods are influenced by the type and degree of processing it undergoes. Natural items are fairly uncompromised if they are mixed with other natural products (such as fruits in a smoothie) or if there are changes in the physical states (such as freezing or crushing). However, if the natural product undergoes a change in the nature of the substance – such as by boiling, adding less natural items, or subtracting items from it, then perceptions of naturalness are significantly changed.

To understand more about the effect of processing on perceptions of naturalness we can turn to psychologist Paul Rozin’s classic experiments with water and tomato paste in which they presented people with different levels of processing of the paste and asked to judge the naturalness:

Original: Tomato paste

Once-transformed: A combination of tomato paste and water

Twice-transformed: The tomato paste that was combined with water, and then has the water removed. The paste is now identical to the original

They found that the ‘twice-transformed’ paste is not only considered less natural than the ‘once-transformed’ item but also less natural than the original – despite being identical in substance.

One explanation for the results of this experiment draws on the role of essentialism in perceptions of naturalness. Essentialism can be defined as “some unique, hidden property of an object by virtue of which it is the object that it is.” If this product has a ‘natural essence’ in the eyes of the consumer, it should be unaltered by changes to its substance. But this ‘natural essence’ can be contaminated, in the case we have described by the processing involved.

Implications

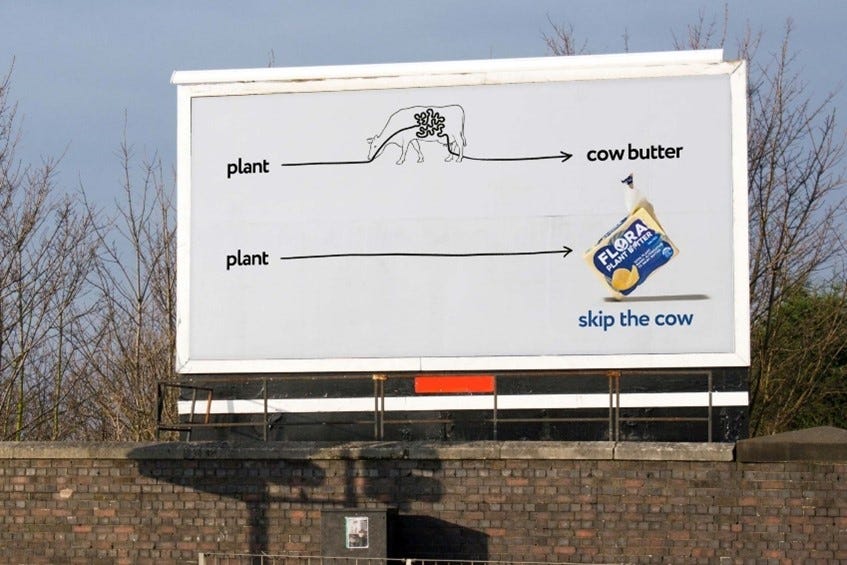

These findings have not escaped the notice of some plant-based food manufacturers who have challenged the notion that their products are somehow less natural. Take the example of Flora whose ‘Skip the cow’ campaign appears to directly reference notions of processing to position their product as the more natural alternative to butter:

What all this suggests is that how we define the boundary between natural or ‘unnatural’ is contested ground: there is no certainty that animal-based foods will necessarily always be considered the ‘natural’ option. How we determine naturalness will be as much, if not more, about how we think about it rather than the food’s functional properties.

This means we need to take consider the wider cultural cues and signals related to naturalness. How we collectively agree on which characteristics we focus on to determine ‘naturalness’ is a behavioural science informed piece of cultural analysis - in a very similar way that we have considered the social underpinning of the way we evaluate risk.

This helps to explain why not all foods that we consider to be natural (such as sugar) are necessarily good for us. And why not all processed foods are bad for us: as Paul Rozin points out in our documentary, Tofu is highly processed yet is typically seen as natural. It is less about the ‘instrumental’ characteristics of the food and more about our ‘ideational’ response: it seems ‘naturalness’ is in the eye of the beholder, meaning that lab-based innovation has much to play for but will need to have a nuanced understanding of the way these things are weighed by the population.