Knowing me knowing you: The human side of AI, data and personalisation

As personal data and AI offer us ever more personalised experiences, what do we make of the personality that is credited to us?

The pages of the website we have recently left greet us upon our return like old friends, the news articles we linger on issue invitations for us to read similar articles, recommendations are offered based on our previous purchases. We live in a world where we have come to expect personalised experiences.

But what do we assume the personalisation we experience tell us about ourselves? If I have an interest in watching crime films then I surely welcome suggestions for other films in this genre. But then if I am being offered crime films with a significant horror element, what is this saying about me? Am I actually a fan of horror films but simply never knew it?

Of course, personalisation is nothing new and AI has long been used to create personalisation from the mass of personal data that is available about us. But the excitement of Chat GPT and Large Language Models more generally have pushed this back up the agenda, not least the range of opportunities it offers for adapting messaging and tone.

Personalisation principles

That we can personalise effectively implies a model of us as knowable, measurable and predictable in terms of what we need and want. As social scientists and researchers, many of us are likely to concur with this view of the world, we can all be known and measured to a greater or lesser extent.

And there is evidence that personalisation can work: research has found that digital targeting improves response to advertisements and performance declines when this is reduced. But there is also evidence that these very same mechanisms can lead to a backlash, with concerns about privacy and surveillance. When a law was introduced in the Netherlands requiring websites to inform visitors of personal data tracking, advertising click through rates dropped likelythese concerns.

Personalisation best practice is something that is important to get right and has explored in detail by behavioural scientists such as Leslie John who suggests the following guidance for companies:

Stay away from sensitive information: We are less receptive to this sort of information being used for personalisation and John suggests in these instances firms should find their customers in ways that do not involve using personal data (for example by advertising on websites these customers are likely to visit.)

Commit to at least a minimum level of transparency: As a general rule of thumb, John suggests that marketers be willing to provide information about data-use practices on request, in a clear and easily accessible way. Doing so creates trust.

Use data judiciously: Customers react poorly when personal information is used to create a recommendation or advertising that is considered intrusive or inappropriate (such as their weight or bra size). Of course, in the case of a clothing brand for example, this sort of information is appropriate and helpful, so context is everything.

Justify your data collection: John suggests explaining why personal information is being collected and how this will facilitate more appropriate and useful advertisements.

Try traditional data collection first: Surveys are a great source of consumers preferences which can then be used to determine where and how to advertise without the need for collection of individual level personal data, both for current as well as potential customers.

Whilst this is a very helpful guide, there is nevertheless still much that we do not know about how people respond to data collection and targeting. While familiar norms from the ‘off-line’ world can help (so the above are all things which can equally apply to in-person transactions), we also need to be mindful that these might develop as online norms change, not least with more nuanced uses of AI.

Mind hacking?

We want to explore what happens when personalisation seems to tell us something new about ourselves. Yuval Noah Harari author of the best-selling book, Sapiens, raises this as a realistic outcome, suggesting that we are in-fact at risk of a technological invasion of our minds:

“There is a lot of talk of hacking computers, smartphones, computers, emails, bank accounts, but the really big thing is hacking human beings, if you have enough data about me and enough computer power and biological knowledge, you can hack my body, my brain, my life. You can reach a point where you know me better than I know myself..”

As such, the notion that we live in a world where it is considered that we can be modelled in a way that tells us something about ourselves we did not already know seems to be a popular one (given Harari is an influential voice). And for a closer to home example, look at the very positive response Spotify Wrapped gets each year as it reveals our listening habits for the past 12 months and how we compare to a wider population of people. There is something there we may have had an inkling of but it can feel good to have it crystallized and played back to us.

This approach is widespread in other fields: for example Zoe is a home test kit that allows you to test your gut, blood fat and blood sugar responses with our at-home test kit, which then build a personalized report on ways to tailor your food intake to your biology. We can also see huge increases in beauty personalisation and other health related areas such as the use of biomarkers for personalised medicine.

Knowing me knowing you

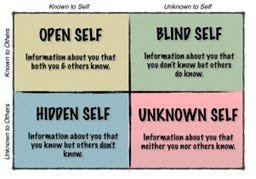

So what we can see is a sense that the increased use of AI based personalisation comes with a narrative that it can tell us something about ourselves that we did not know. The Johari Window is as a useful framework for exploring the impact of personal data on the organisation-brand relationship. It was created in the 1950s by psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham (the framework is named using a combination of their names).

The complexities for us come in the column section ‘Unknown to self’: we are aware that there are things we do not know about ourselves (e.g. I am not sure I would like a new music artist if I had not heard them) and the music company may in fact have a sense of whether I am likely to enjoy them based on other things I have listened to. Indeed, this is of course exactly the principle that is used for recommendations by many organisations.

A very tangible example of being informed of something we may not know about ourselves is the way our banking behaviours may reflect digital patterns that signal illnesses such as dementia. For example, one study of 81,000 Americans aged over 65 found that missed credit card payments could show up a diagnosis as far back as six years in advance of a dementia diagnosis. Sam Kunjukunju, the ABA Foundation’s vice-president of consumer education, suggests:

“Bankers are not medical professionals . . . but they may notice when patterns are off, sudden unpaid bills or uncharacteristic attempts to wire large sums of money”. If necessary, they can delay a transaction or contact adult protective services.

How does it feel to be told these things?

The receiving of this type of personalised information can feel ‘uncanny’: as tech critic Sara Watson suggests, we have no real way of knowing whether this is based on information that is specific to us individually. As she points out, ‘We don't often get to ask our machines, "What makes you think that about me?"’.

Of course, this complex relationship we have with personalised information reflects a disparity in access to this information held in personal data and the analysis of it. Which means that if that person has access to this information then I may reasonably be hesitant about dismissing it too readily. And if the tools that have been used to are imbued with ‘intelligence’ then I may be doubly unsure if I should dismiss this out of hand.

Gas lighting?

Which gets particularly tricky when we are presented with material that we assume is personalised to us based on our own data but is in fact not quite the case. Forbes magazine recently reported that one social media platform has a “heating feature” —a “button that can make anyone go viral.” This, it is claimed, allowed staff to secretly hand-pick specific videos and supercharge their distribution, using a practice known internally as “heating.” This directly influences the users’ personalized feeds which the user assumes (as this is how they are positioned) as being determined by an algorithm to reflect your preferences based on your behaviour in the app. As tech critic Rob Horning has pointed out:

People are encouraged to believe that the algorithm discovers something special about them and shapes their experience on the app around their proclivities. But as “heating” illustrates, it turns out that what is “For You” may have less to do with who you are and more to do with brand and creator partnerships.

If this is the case (and it is not clear how widespread this practice is), why do we not challenge the recommendations being made for us? After all, perhaps if it is not reflecting then maybe we see its lack of relevance for us.

The answer to this is unclear: perhaps we do in fact often dismiss personalisation, as research suggests we still call on friends and family for recommendations on what to watch, with 42% of TV series viewers saying that in-person conversations with friends and family are helpful to make their choices.

But at the same time, there is overwhelming survey evidence that suggests we want personalised experiences and we enjoy the upsides that they offer, which seems to suggest that we may well attribute what has been presented to us as reflecting our own tastes and preferences. In other words, we have a reverse fundamental attribution error on ourselves. We over-emphasise the situational factors (i.e. what the personalisation is implying about us) and under-emphasise our own understanding of our own character, preferences, desires and so on.

The area of narrative identity is also useful here, being the internalized and evolving story we create events to explain how we are the person that we are becoming. This narrative can of course be influenced by the apparent stories that are being told to us in the process of personalisation.

Implications

If we give weight to a piece of information, on the basis we assume it is based on our personalised preferences, then it is not a stretch to consider we are likely to be more open to it. If we choose to watch one TV series rather than another, then little is lost. But perhaps in other areas such as mis / disinformation, the implications are greater.

But counter to this, if personalisation becomes discredited and people start questioning whether personalisation is in fact a more standardised promotion then the upsides (which people often consider are positive) could rapidly dissipate.

More widely, our relationship with AI tools is a complex one and the opportunity for personalisation that Chat GPT seems to offer means it could get even more complex and nuanced.

Companies are often asking the question: ‘How can I ensure best practice to deliver effective personalisation’. This remains important but we may find there is an increasing power struggle between our own view of ‘how we are’ versus the right of organisations (and others with access to Chat GPT and similar tools) to de-facto tell us ‘who we are’.