The business of behavioural science

To be strategically relevant we need to be able to scale the discipline

Behavioural science is a discipline that can feel steeped in bespoke expertise. Expert take on the literature with a bespoke solution is often the expectation of a behavioural science practitioner, in a way that is less the case on other activities.

I would argue that, to some extent, the bespoke expertise model common in behavioural science is a function of its relative nascence as an applied discipline. In their book, The Future of the Professions, Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind discuss the way any discipline goes through a number of stages from bespoke and expert led through to ‘Systematisation’ where technology is used to deliver solutions.

I would argue that market research went through much the same process over the last fifty or so years – from a bespoke expert based model to one which has many element which are delivered by technology. But as we know from this larger field, these stages are not mutually exclusive, there is room each to operate.

If the behavioural science profession is to play a key strategic role for brands, governmental organisations and non-profits, then it needs to consider how it moves from the current ‘craft-expert’ position, individual ad-hoc pieces of work executed by expert staff. A craft-expert model is hard to scale and in fact most management consultancies, once the epitome of this, have now transformed to much more efficient, scalable models.

Why do we need to scale? Because the opportunity for behavioural science is immense – but needs to be accessible to organisations across their geographic and organisational footprint. Without providing tools to a wider set of people in the organisation there is a danger that it has limited relevance and impact.

All major professions have a long track record in standardization – essentially routinizing expertise for later re-use. The remarkable growth of market research over the last three decades has largely been built both by standardization of process (e.g. checklists, manuals, standard guides) as well as substance (e.g. templated surveys). This move is not purely driven to cut costs but is also to prevent avoidable errors, ensure consistency and prevent duplication of work. Of course, this has the benefit of reduced reliance on a limited number of professionals. Standardisation does not replace ‘craft’ in its entirety but focuses it on those parts of the process where it has most value.

Some aspects of behavioural science appear to be harder to standardise than others. Measurement of these automatic ‘system 1’ effects (e.g. heuristics and biases) are very difficult to achieve in a routinized way. Given that the way system 1 effects (and influences) are automatic, they are not readily accessible through the use of direct questions. Instead, behavioural economics typically identifies and explores these phenomenon by using experimental designs or expert judgement – both of which require a great deal of custom ‘craft-expert’ work and are hard to standardize (and therefore scale).

One area where behavioural science has an opportunity to leverage a standardization strategy is in the area of behaviour change. Part of the reason for this is that in order to develop behaviour change strategy for our clients, an holistic, systematic method is used that incorporates an understanding of the nature of the behavior to be changed, underpinned by a theory of behavior (from behavioral science) and an appropriate system for classifying interventions. The holistic element means that measurement is much more straightforward; the systems method gives a consistency which means that expertise can be standardised (with appropriate levels of quality control and governance).

Of course, the immediate challenge is to ensure that we are able to generate good enough, the same or perhaps even better outcomes through the process of standardization. This is not an inconsequential matter of course and there is are risks of getting it wrong. But then there are also risks with a purely expert led model where we are reliant on the skills, attention and capacity of a small number of individuals.

The Susskinds suggest that many practitioners can be most comfortable with a craft-expert role – with a love for the content and process, exploring ideas and engaging with academics (what the Susskinds call the ‘process’). We see this in a range of professions from law and accounting to management consulting and market research. And, of course, there will always be an ongoing and critical need for this.

However, there is a danger that we get side tracked by the ‘process’ itself. To illustrate this, while we may get just the same quality coffee from a Nespresso machine as from a barista, we enjoy the process of the barista making the coffee. There is something about the process which has value for us.

But for the profession to scale as a serious strategic partner then we need to have a focus on the ‘outcomes’; if we get too side tracked by the process then we are in the realm of interesting and useful rather than a strategically critical partner for driving key outcomes. Otherwise we will be in the realm of ‘this is interesting but what do I actually do with it’. Of course, these things are not mutually exclusive but, surely, we need to challenge ourselves that for the successful application of behavioural science at scale, then we need to focus on outputs rather than the process.

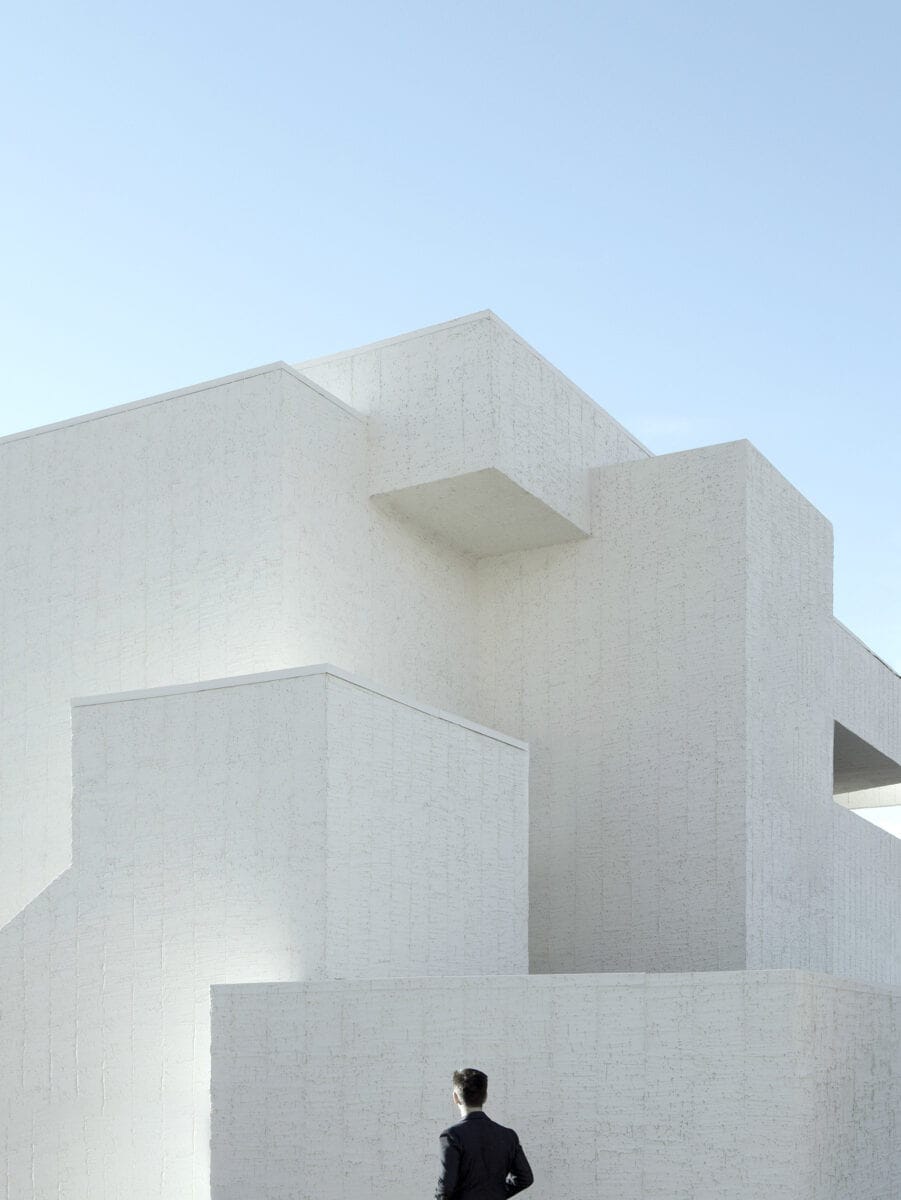

Picture of the week: Mihn T’s work showing a person within concrete merging with sky, perhaps reflect a range of themes that seem relevant for the COVID time we find ourselves in.

News

I liked this article exploring futures – a lot of interesting concepts from Feral Futures to Precarious Presents – definitely worth a read

When we do behaviour change work we often talk about the structure of the environment and how this is important for understanding behaviour. With this in mind, the news that Apple now receives an estimated $8 billion to $12 billion in annual payments —in exchange for building Google’s search engine into its products is surely a highly vivid example of this.

Reads and views

I am curious about this book: As the world finds itself drowning in data, researcher Demetria Glace has teamed up with food technologist Emilie Baltz to unpack the origins of information leaks, through the universally appealing metaphor of food.

Minh T’s work can perhaps seem evocative of the tensions in the world we inhabit, of humans operating in a space that can often feel as if it has few obvious means to navigate it.