The changing landscape of debt and the psychology of shame

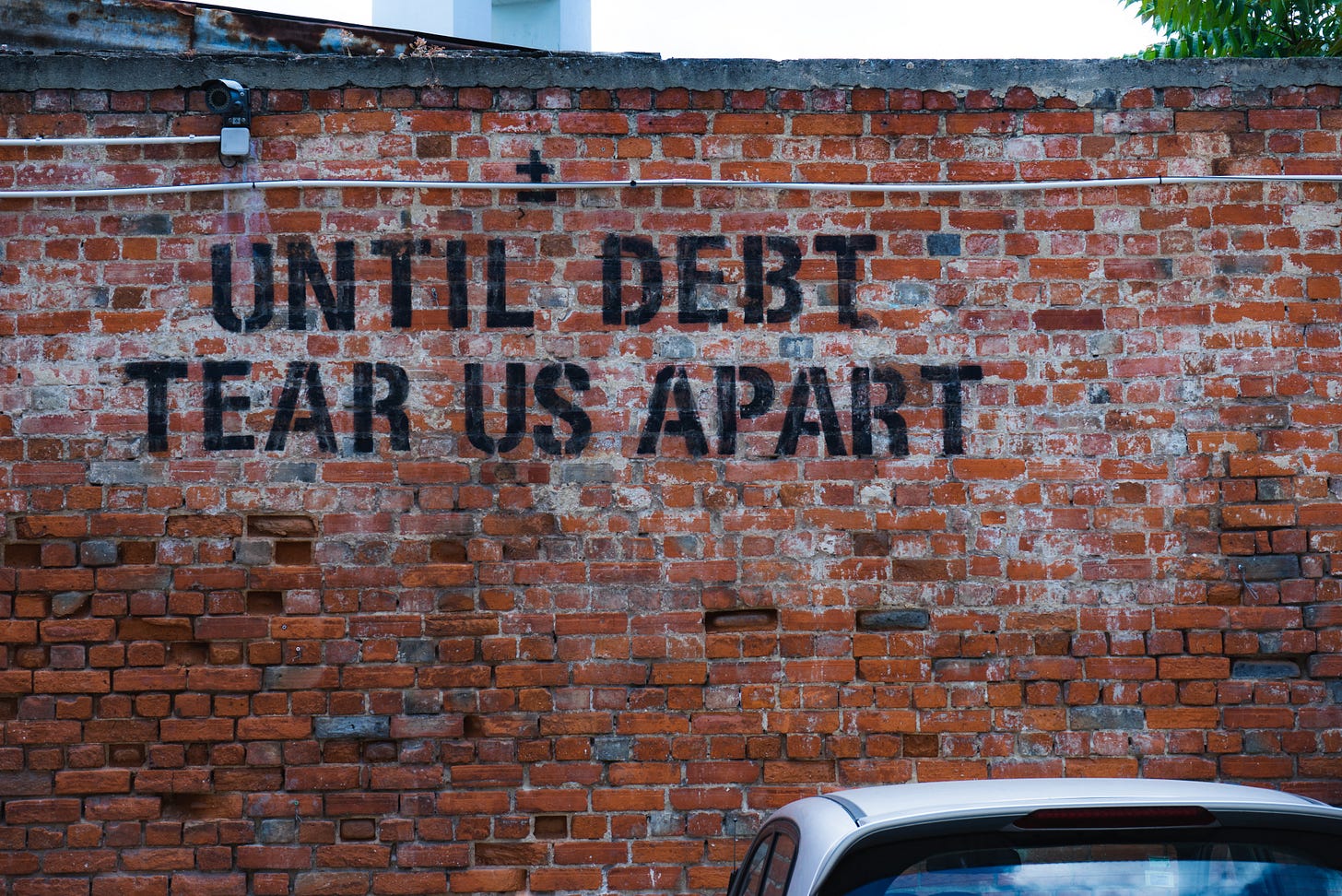

For many, (but far from all), debt is frequently associated with shame: but as the cost of living crisis leads to household budgets simply not balancing, we ask if this will change.

Debt is a topic that has long attracted the attention of behavioural scientists, eager to find ways to support people to manage their difficult circumstances and generate greater financial wellbeing. Understanding what to draw from the broad range of research available (see Abigail Sussman and Hal Hershfield for examples) is important given the environment we are in, which is expected to get rapidly worse.

Of course, in some ways debt in itself is arguably not a bad thing – our entire financial system is built around it and there are few other ways in which most people can make significant purchases. The difficulty comes when servicing the debt is not sustainable. A combination of interest rate increases and inflationary pressures is likely to do just this: indeed, people on middle incomes have been predicted to be struggling in this environment. Given this perilous state, understanding the psychology of debt is clearly very important. And at the same time, the changes we are seeing unfold help us as to better see the psychological mechanisms that shape the way we behave in relation to debt and, more generally, how emotion is constructed.

The focus of behavioural science on debt

We have previously pointed to the work by Anne Custers who has explored the issue of debt management. She makes the point that leading behavioural science journals tend to concentrate on a narrow body of theory that has its roots in neoclassical economics and cognitive psychology (such as informational determinants, goal-related theories and mental accounting theory.) Fundamentally these take a cognitive processing model of human behaviour which typically locate the problem in the individual.

Custers suggests this is congruent with a dominant assumption that people are in fact able to pay but are either not willing to do so, or they are not sufficiently well equipped to structure their finances and live in such a way that they are able to. This leads us to a process of ‘fixing’ the person using the tools available: this might be, for example, the design of letters so that people are better able to understand the implications of their behaviour and the importance of financial management.

Of course, as regular readers of this blog will sense, this cannot be the full story. At a time where there is such pressure on household budgets, we simply cannot ignore the wider environment people live in. There is a great deal of evidence that people living on low incomes have a make a complex trade-offs concerning their spend and in fact spend a great deal of time planning their spend in a sophisticated way. It is not simply that they are not willing to pay but may well simply not be able to do so.

The shame of debt

And this is also not the full story. As debt campaigner Astra Taylor wrote:

Conversations about debt are never purely about economics. They are always, also, conversations about power, morality and shame.

This suggest that to properly understand debt we need to move beyond a conversation about cognitive mechanisms and consider the wider context within which this occurs. The leading thinker in this area was anthropologist David Graeber, whose book on the topic is regarded as one of the most informed and thoughtful.

He described debt as “an exchange that has not been brought to completion.” This is neither a good nor bad thing in itself. On the positive side, debt puts people who otherwise would have nothing to do with each other into relationships:

“Debt is what happens…when the two parties cannot yet walk away from each other, because they are not yet equal. But it is carried out in the shadow of eventual equality…. In fact, just about everything human happens in between-even if this means that all such human relations bear with them at least a tiny element of criminality, guilt, or shame.”

We can take this to mean that we are all in debt to each other in some way: having a relationship with another person inevitably requires us to repay a favour, honour a secret, return a complement and so on. This is the stuff of human life that keeps us all knitted together. Given that so much human activity is so often about being in relationship, then if there is no longer a possibility of returning to equality a gap is created:

“This is what makes situations of effectively unpayable debt so difficult and so painful. Since creditor and debtor are ultimately equals, if the debtor cannot do what it takes to restore herself to equality, there is obviously something wrong with her; it must be her fault.”

And this is where we start to see the way that debt relates to shame: being in debt in the myriad of small but very human ways is how we manage the day to day of our human relationships. So if we are in a position where we cannot repay, then this feels problematic. Indeed, the connection with shame becomes even clearer when we look at the provenance of the word ‘debt’: many are alternatives or "fault," "sin," or "guilt." So as Graeber points out:

“…just as a criminal owes a debt to society, a debtor is always a sort of criminal.”

Of course, he does not mean this literally, but this is the role in which the debtor is often intuitively cast in our minds. No wonder that shame is so intricately linked to debt, it is culturally very closely linked to notions of inequality and hierarchy.

The inequality of shame

But debt does not automatically have this ‘baggage’: indeed in a recent podcast, Jesse Eisinger, senior editor at ProPublica, pointed out that the billionaire class often avoid tax by going into debt through borrowing against their wealth. This is a perfectly legal tax avoidance strategy, (you are not taxed if you're borrowing against your wealth). This seems a successful strategy, with Eisinger and team finding that, on average, people in the US pay roughly 15% in federal income taxes, and the ultrawealthy pay 3.4% when compared to their wealth growth.

While we don’t have any data to support this, it is hard to imagine the ultrawealthy having feeling of shame about their debt. This disparity in feelings of shame about debt matters: it makes it clear that there is nothing pre-ordained about feeling this way. Being in debt does not need to automatically lead to shame. Indeed, it is perfectly normal for many other people to enter situations where they incur debt without shame (e.g. mortgages, car purchase financing).

But it is nevertheless a widespread emotion for people on low incomes – Custers notes the way this is often in fact leveraged by debt collection agencies with subsequent negative impacts on wellbeing. Generally there is a great deal of complexity here in morality judgements about money; for example found people receiving government support were seen as less moral when buying ethical goods. We will likely unpack these judgements further in later posts but suffice to say for now that there are deeply embedded moral judgments linked to our financial behaviour and debt is perhaps the pinnacle of this.

A new understanding of emotion

We could argue that shame is particularly strong emotion as it is vulnerable to wider social and cultural mechanisms given that is comes from feelings of inadequacy relative to others; if others are not present (in our minds at least) then we do not have the same shameful response. It is an intensely socially-derived emotion that results in a high degree of self-blame.

But perhaps shame and its relationship with debt illustrates even more broadly something about the social nature of emotion. We have talked before about the shift we are seeing in explanations of emotion: early psychologists looked at emotion in terms of innate drives, our emotional states seen as related to the history of the species itself or to the learned history of us as individuals. This is linked to an assumed notion of a universality of emotions which was popularized by Paul Ekman. According to these accounts, emotion is very much within the individual - an ‘inside out’ model as it were, an individual, ‘contextless’ act.

More recently, psychologists such as Lisa Feldman-Barret, have suggested that we do not construct our emotional concepts individually. Instead, Barret suggests that our emotions are a function both of our internal states as well as external facets of the world we live in. On the same lines, a recent book by Batja Mesquita sets out the way that psychology has relied on a Western and individualist model of emotions: the MINE, or ‘Mental, INside the person, and Essentialist,’ model. This sets out that the most important mechanism of an emotional experience takes place firmly in the individual.

The alternative to this, and the way that most non-Western cultures conceive of emotions, is OURS: ‘OUtside the person, Relational and Situated.’ For Mesquita, the OURS model, requires us to look ‘outward, rather than inward’ which she considers a more appropriate model for emotion than the MINE model. Mesquita maintains that we need to see emotions as culturally constructed experiences taking place between people that varies between cultures and social contexts.

In the context of the deeply social and cultural nature of debt, the emotion of shame through an OURS lens seems to make sense. And whilst we are looking at the emotion of shame in relation to debt, this lens is surely an invitation to think more broadly what the wider ‘outward’ structures are that explain a range of other emotions in other contexts.

What does this mean for how we feel about debt?

Given there is a compelling account for emotion that it is not only ‘inside-out’ but also ‘outside-in,’ then logically we can see that if the environment changes then the way we emotionally respond to it will also change. This returns us to where we started, setting out how the cost of living is pushing many people into debt. It is increasingly apparent that it is simply structurally unsustainable to have balanced household budgets for a rapidly growing proportion of the population.

In an environment where a relatively small (and frankly marginalised) proportion of the population are experiencing ‘problem debt’ then it is all too easy to characterise this is a personal, individual issue not the result of wider economic conditions beyond their control. It is now all too apparent that it is structural issues that are causing financial distress, not some individual deficit.

At the same time we can see an increase in campaigns such as ‘Can’t pay won’t pay’ that actively propose that people incur debt through non-payment of utility bills. In the US President Biden has introduced a student loan relief plan which will remove a significant economic challenge for millions of people. Taylor suggests we are potentially seeing a psychological shift that could embolden those who find their obligations overwhelming to engage in collective action aimed at winning more relief and changing the policies that make indebtedness so pervasive.

What can we conclude?

The emotion of shame and its relationship to debt is a huge issue that has a significant impact on peoples lives. It not only discourages people from seeking help early but can have a negative effect on the wellbeing of people who often already have a difficult ‘mental environment’ to navigate.

A range of private and public sector organisations have sought to address the issue moving the discussion of money away from one of shame and self-blame, aiming to make it a more socially-acceptable subject and in doing so supporting better financial capability and wellbeing.

Nevertheless, there is a risk that a focus remains on the individual being expected to manage this, albeit with some support. This continues to reinforce the notion that debt is a function of the individual’s ‘deficit’ in some form and therefore pushes us into a scenario of solutions that are surely at risk of being a mismatch with the root causes of the issue. It is becoming increasingly apparent that the way forward needs to have a focus on structural solutions, with recent interventions by governments to reduce energy bills being part of this.

We can also see the way that arguably the psychologization of debt as individual deficit perhaps explains why current tax policies typically subsidize saving behavior (e.g., through a tax-benefits) but the same benefits do not apply for paying off debt. More creative thinking could be applied to policy initiatives which better align with the sources of the problem (offering structural support for a structural problem).

David Graeber, set out the way that throughout history there have been periodic debt amnesties, (‘Jubilees’) where sovereigns would periodically wipe away debts. Debt relief and other forms of support were less about the culpability of individual debtors and more a tool offering a practical way to recover from crises and avert societal collapse. With Biden’s action loan relief plan we may be seeing early signs of a more fundamental rethink, perhaps offering a more radical approach to policy making.

One of the wider lessons here is that we need to be careful not to over-psychologise something that can be better explained by an examination of the wider structural landscape. Behavioural science helps us here by supporting us to inspect the behaviour, unpack what is happening and allocating causality behind the behaviour in a more meaningful way.