The Price is Right (or not): How pricing shapes brand relationships.

The price of something is more than a number, defining the relationship between buyer and seller.

Pricing is more than just a number—it is a signal, a strategy, and a psychological lever that shapes how consumers feel, react, and behave. Whether it is the premium positioning of Stella Artois' "Reassuringly Expensive" campaign that ran from 1982 to 2007, reportedly driving a staggering 192% return on advertising investment, or the controversy over the dynamic pricing used to sell Oasis ticket prices, where Liam Gallagher suggested fans could pay for "kneeling tickets," pricing is a deeply emotional and often divisive issue. At the other end of the spectrum, rock-bottom prices, such as those seen in fast fashion, raise ethical concerns for consumers, while climate change and supply chain pressures are making essentials like coffee more expensive than ever.

The impact of pricing decisions extends far beyond purchases from commercial organisations. Government policies, such as Scotland's minimum alcohol price increase from 50p to 65p per unit, attempt to influence public health behaviours. Governments around the world are introducing congestion charges and dynamic road pricing to manage traffic flow, reduce emissions, and influence commuter behaviour.

And there has been much discussion about topics such as 'greedflation' and shrinkflation, where brands stand accused of quietly raising prices or reducing product sizes. Pricing attracts intense consumer scrutiny, not just in terms of what is charged, but how pricing is structured, framed, and justified, leading to an issues of perceived fairness, exclusivity, and arguments over morality.

Yet, despite its prominence in our lives, pricing has been called one of the least studied and most overlooked elements of the marketing mix. But if we are to properly understand behaviour, trust, and relationships between buyers and sellers, then pricing and its psychological and social effectssurely need much more scrutiny.

Current status of pricing research

Most contemporary psychnology research on pricing focuses on how prices are framed; in fact, the literature on this is significant: a good case of this is 'charm pricing', which, for example, finds that prices ending in .99 (e.g., 9.99 instead of 10.00) create a perception of lower cost, making products seem like a better deal. This effect, known as ‘left-digit anchoring’, occurs because consumers read prices from left to right and tend to focus on the first number, perceiving 9.99 as significantly cheaper than 10.00, even though the difference is just one cent.

Research also shows that odd pricing (e.g., 4.97, 19.99) is associated with discounts and bargains, while rounded pricing (e.g., 20.00, 50.00) signals quality and premium positioning. Additionally, studies suggest that charm pricing is more effective for emotional purchases, whereas rounded pricing works better for rational or high-involvement decisions (e.g., luxury goods or professional services).

However, outside of this, pricing has received little attention from academia and practitioners, and there have been few empirical studies on the topic.

The reasons for this are subject to debate, but it may well be in part (paradoxically) due to its importance. Price can have a strong and rapid impact on sales volume and market share, much faster than the other marketing elements. As such, this can lead to risk aversion: we experiment with it at our peril. There are other factors, too, of course: pricing is complex, secretive, and difficult to study empirically, both as companies rarely share data and experiments carry financial risks. Moreover, it sits at the intersection of economics, psychology, marketing, and finance, meaning no single discipline 'owns' it.

But perhaps more fundamentally, classical economics suggests that supply and demand naturally dictate prices, making it seem like businesses have limited control.

The myth of market-determined prices

To properly understand the psychology of pricing, it is useful to first examine its historical roots. The conventional narrative suggests that prices emerge naturally from supply and demand, aligning with Adam Smith's concept of the "invisible hand" of the market. However, David Graeber has long challenged this foundational view, particularly the idea that money, and therefore pricing, evolved from barter. Instead, he argues that pricing has historically been shaped by social relationships, power dynamics, and institutional structures rather than purely organic market forces.

However, the dominance of the view that the market sets prices can determine the direction for brands who often anchor their pricing to existing price points in the market, as they assume competition and historical precedent dictate appropriate levels. This helps explain the widespread use of web crawling to track competitor prices, ensuring that businesses remain aligned with, or slightly undercut, their rivals. It also reinforces the continued popularity of cost-plus pricing, where businesses set prices based on production costs plus a fixed margin, following the logic that pricing should be a predictable function of costs.

However, in Graeber's book Debt: The First 5,000 Years he demonstrates that debt-based exchange systems existed long before coined money. And, in fact, pricing has always been political. From Mesopotamian grain taxes to medieval tally sticks, money functioned as a tool of governance, not an organic market development.

This means that money has historically been about power and obligation rather than a neutral exchange, so pricing is not neutral: it is as much about relationships, power, and loyalty. And one aspect of pricing is perhaps most psychologically significant: fairness.

Pricing and fairness

Fairness is certainly a consideration in the rapidly developing space of dynamic pricing, where platforms use real-time surveillance to adjust prices, ensuring consumers pay the highest amount they can tolerate at that moment. Industries such as transportation, ticketing, and accommodation have adopted these practices, charging more based on urgency, location, and browsing history. Alongside this, there is a rise of so-called' junk fees', such as additional charges for basic services that were once included. 'Shrinkflation' has also hit the headlines, where products are reduced in size while prices remain unchanged, with critics claiming this makes it harder for consumers to understand what they are actually paying for. In some sectors, it is also argued that there is deliberate collusion to inflate costs beyond what market conditions justify.

Taken together, these practices suggest that pricing today is in danger of being considered by customers as too often being less about fair exchange and more about how much companies can charge. And this is not simply about affordability (which is important in its own right, of course) but legitimacy—the process of determining whether the way prices are set. A high-profile example was how ticket prices were set for the pop band Oasis's reunion tour, where dynamic pricing was used. There was significant public backlash across social media and the press, with fans reporting ticket prices surging from €160 to €400, prompting political and legal scrutiny.

If we look at the psychology of this, we could speculate that many (but, of course, far from all) of the people buying Oasis tickets could afford the higher end of the prices. After all, most tickets for significant music events are in that kind of price bracket. However, perceptions of fairness are as much about the final price as they are the process that determines this.

Research by Markus Paulus highlights how deeply ingrained our sensitivity to fairness is; when faced with unequal resource distribution, even young children are more likely to reject an offer entirely than to accept an unfair split. This distinction between ‘distributive’ and ‘procedural’ justice is crucial in understanding why some pricing models provoke outrage while others, even if they result in high costs, are tolerated.

On this basis, pricing strategies result in people suspecting they are being charged 'what they can tolerate' rather than a price reflective of fair value, which can lead rto trust and legitimacy starting to crumble. This is where procedural justice becomes critical. If people feel that the process behind a price hike is unfair, whether through price-fixing scandals, hidden fees, or personalised pricing that penalises certain consumers, they are more likely to resist or be critical of the vendor, even if they can technically afford to pay.

But of course, the relationship that price sets up with the brand is more multifaceted than simply being about fairness: understanding how different pricing strategies influence different aspects of our relationship with a brand is something we now turn to.

Enhancing relationships through price

Consumer decisions are often considered by behavioural scientists to not be purely rational or pre-defined but are instead constructed in response to the decision environment. This means that pricing structures can actively shape consumer preferences, expectations, and trust: pricing is not purely about revenue but has a key role in strengthening relationships.

Supermarket loyalty card pricing is one of the most widespread examples of ‘relational pricing’, offering exclusive discounts, rewards, and personalised pricing to frequent shoppers. Major retailers like Tesco (Clubcard Prices), use this model to create a sense of belonging and preferential treatment, subtly shifting pricing from being purely transactional to a membership-based relationship.

Another (and much more niche) example is Pay-What-You-Want (PWYW) pricing, adopted by some performing arts organisations. Allowing audiences to self-determine ticket prices means that cultural experiences can be more financially inclusive, and this process fosters broad goodwill. Of course, theatres and museums have also long implemented sliding scale pricing, where people pay based on their financial ability, to encourage diverse participation by removing economic barriers.

In retail, IKEA's Buy Back & Resell programme is an increasingly popular approach to relational pricing by major retailers. It allows customers to return used furniture for store credit, promoting sustainability while keeping products affordable. Another example is Nike's Refurbished programme, which resells slightly worn or returned sneakers at a lower cost, meeting consumer demand for sustainability whilst building a strong brand relationship.

These strategies demonstrate that pricing can be more than a transactional decision—it can be a tool for building relationships, fostering brand loyalty, and promoting equity.

A framework for relational pricing strategies

Pricing strategies can of course be helpful or unhelpful in building relationships between buyers and sellers. For example, dynamic pricing can seem punishing and alienating in some circumstances (e.g., buying a ticket last minute), but it can also mean that people can game the system and find bargains. When Disney adopted dynamic pricing at its parks, for example, guests found that they could schedule their holidays for periods when the park would be less busy.

The sheer range of pricing strategies available suggests it is helpful to place them into a structured framework to better understand how to align pricing decisions with a broader brand strategy. By categorising pricing approaches based on their impact on brand relationships, sellers can more effectively design pricing models that reinforce their desired brand position.

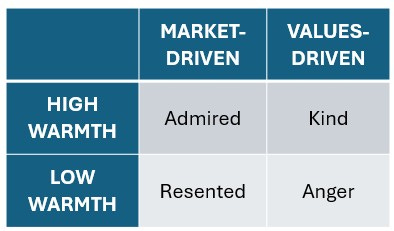

One option for this is the Stereotype Content Model (SCM), developed by Susan Fiske and colleagues, a psychological framework that explains how people perceive others based on two key dimensions:

Warmth: Is the person (or brand) perceived as friendly, trustworthy, and well-intentioned?

Strategic orientation (known in SCM as 'competence’, reworded here for clarity): Does the person (or brand) project innovation or aggressive market leadership (market-driven), or do they prioritise ethics, community, and inclusivity over competitive advantage (values-driven)?

The SCM was originally developed to explain how humans stereotype groups, but it has since been widely used to understand consumer perception of brands. People form quick impressions of brands the same way they do with individuals, evaluating whether they are trustworthy (warm) and market-driven or values-driven (strategic orientation). In a brand context, the SCM can be used to explain how consumers categorise brands and how pricing influences these perceptions. We can speculate that different pricing strategies push brands into different quadrants, reflecting how consumers feel about them (see below).

Admiration: Brands that fall into the High Warmth, Values-Driven quadrant could include supermarkets with consistent, low-cost pricing models, signalling fairness and reliability. By maintaining stable, transparent pricing on essentials, they communicate that they prioritise customer well-being over opportunistic profit-taking, reinforcing trust and long-term loyalty.

Envy: Brands that operate in the Market-Driven but Low-Warmth quadrant, such as those using surveillance-based dynamic pricing, appear powerful and efficient but also ruthless. When companies adjust prices in real time based on consumer behaviour or willingness to pay, such as airline ticket fluctuations, consumers may recognise the brand's intelligence, but there is a danger they also feel manipulated and exploited rather than valued.

Paternalistic: In contrast, businesses using pay-it-forward pricing models, such as coffee shops or arts organisations, allowing customers to subsidise purchases for others, fall into the High Warmth / Values-Driven quadrant. These organisations are often perceived as ethical and generous but may struggle to command premium pricing or be viewed as strong market players because they prioritise signalling their values over a market orientation. As such, consumers may often support them out of goodwill rather than brand superiority.

Resented: Finally, brands that engage in what can be seen as exploitative pricing tactics, such as shrinkflation or excessive hidden fees, may be pushed into the Low-Warmth, Market Driven quadrant). These businesses, like ticketing organisations with opaque pricing structures or some fast fashion retailers with opaque supply chain practices, are seen as cutting costs at the consumer's expense while failing to offer meaningful value in return. While customers may continue purchasing out of necessity, they could also be disengaged and eager to abandon the brand when a viable alternative emerges.

We suggest this framework as a starting point for thinking about price and its impact on relationships. Other frameworks may, of course, also work well. Still, the wider and most important point is that relationship frameworks can be adapted very effectively to encourage more strategic thinking about the impact of pricing and how it shapes the way consumers relate to and evaluate brands.

Changing notions of money and price

Of course, we could conclude here, but some developments deserve further discussion as they have the potential to transform the way we approach pricing. To explore this, we return to David Graeber's assertion that societies originally relied on trust-based credit systems before coinage existed. Today, we can start to see how alternative pricing systems have emerged that move beyond pure monetary exchange.

As we have covered previously, platforms like Twitch, YouTube, and Patreon allow users to send digital tokens, 'super chats,' or tips to content creators. While these transactions involve money, they also function as gifts—expressing support, appreciation, or fandom. Online games further illustrate this shift, featuring in-game currencies and virtual items that can be earned, purchased, or gifted. These assets serve a functional and symbolic purpose within digital communities, allowing players to show respect, build relationships, or express their identity within the game's social hierarchy.

While these developments appear largely confined to digital platforms, stakeholder-based pricing models in traditional finance and retail reflect similar participation and shared benefit principles. UK building societies, for instance, operate on a mutual model where members collectively benefit from lower fees, exclusive mortgage rates, and better savings returns. These institutions reinvest profits to provide value back to their customers, reinforcing pricing as a relational and trust-based system rather than a purely transactional one. Similarly, brands like BrewDog's 'Equity for Punks' initiative offer shareholders exclusive perks and discounts, aligning financial commitment with consumer engagement.

So, to some extent, we can see this as a fundamentally different approach to "price"—one that integrates social relationships, participation, and trust into the pricing mechanism itself. Whether through digital tipping, in-game economies, mutual financial models, or consumer-investor programs, these pricing strategies reflect a return to early economic systems, where value was as much about social bonds as it was about financial exchange.

Conclusions

Historically, pricing has never been neutral – if we travel back in time, then prices were often set on the spot, with the shopkeeper assessing the amount the customer would be willing to pay. John Wanamaker's invention of standardised pricing in 1861 was not just about convenience—it was a moral argument, an attempt to level economic playing fields by eliminating bias from sales transactions. He famously said

"If everyone was equal before God, then everyone would be equal before price."

The notion that we can eliminate the messy business of setting prices and the unfairness that could result from favouritism gave rise to the idea of fixed pricing as a fair and transparent system, one where consumers would not need to negotiate or worry about being overcharged based on their appearance, background, or perceived ability to pay.

However, as pricing has evolved—through dynamic pricing algorithms, personalised offers, and hidden fees—we find ourselves in a world where prices are once again fluid, variable, and tailored to what a company believes an individual will tolerate.

Which brings us to the topic of haggling - where price is not just an economic figure but a relational tool shaped by trust, negotiation, and social cues. In traditional marketplaces, price emerges through direct interaction between buyer and seller, with each side testing the limits of what the other is willing to accept. Unlike fixed pricing, haggling makes the price a fluid outcome of the relationship between the two parties, where factors like loyalty, persuasion, and social status influence the final number.

The question is whether modern pricing mechanisms perhaps bring elements of haggling into the digital age. Right now, instead of a two-way negotiation, companies are able to adjust prices in real time based on demand, urgency, location, and even browsing history—effectively haggling with the consumer but without their participation. In traditional haggling, the consumer has some control over the final price, whereas, in many modern pricing strategies, consumers are arguably simply tested to see how much pain they will tolerate. However, there is also theoretically a way in which buyers are de facto able to haggle by holding out and seek to anticipate change in pricing. Prospect theory comes into play here where a sudden price increase in response to high demand (e.g., last-minute airline tickets) is perceived as a "loss" for consumers, while a temporary discount (e.g., early-bird sales) is seen as a "gain"—even if the net revenue outcome is the same.

How this relationship is designed and managed will impact on the longer-term relationship with the buyer. But most broadly we could consider that developments in pricing are creating more opportunities for dialogue, whether through loyalty programs, membership pricing, or models that reward long-term engagement.

The question remains: Do brands (and the public sector, albeit from a different perspective) see the opportunity to approach pricing as a tool for building relationships or as a means of maximising short-term returns but with longer-term relational consequences?