What does wellness mean anyway?

The team is widely used but lacks a shared, fixed meaning: this means a lot of contested ground and challenges concerning who wellness is for

Wellness is a term that is used to describe a huge range of areas as diverse as health, finance, dietary supplements, yoga, ‘chemical-free’ beauty products and clean eating, to name just a few. How do all these disparate topics all come to be clustered in this way? What is the underlying logic that puts them all under the heading of wellness? Perhaps wellness does not have a fixed, shared meaning, in which case the things that we each see as legitimate to be considered as wellness may well vary depending on your point of view: one person’s notion of wellness may well be very different to another person’s. This means we can find ourselves in the position where some groups feel that others are defining wellness in a way that excludes them.

To help us unpack this, it is worth considering how we classify things – and then explore how this has significant implications for the way we go about wellness.

How we decide to group things

Psychologists Douglas Medin and Andrew Ortony coined the term ‘psychological essentialism’ to reflect our tendency to think of the world as divided into discrete kinds of things, each of which has as ‘essence’. By this we mean an underlying quality that makes it part of a category of things.

Biological species are a prime example. It seems like a near universal human activity to organise the animal kingdom into species. But what gives an animal membership of a species? For example, what is it that makes a certain animal a porcupine? It’s not its quilly appearance as a porcupine without quills is still a porcupine. We tend to believe tacitly (and often explicitly) that what makes an animal a member of a certain species is less about its outward appearance but instead it is some deep fact about it – in this case, the porcupine essence – even though we might have no coherent idea of what that essence actually is.

This tells us something about wellness: we have a sense that a bunch of different things fit into this category we call wellness, but we do not really know what it is that determines this. In a recent book, Colleen Derkatch interviewed 40 Canadians who regularly take natural health products and are actively interested in wellness. When they were asked to define wellness, she writes that their definitions were “thoughtful but nonspecific and often circular, with frequent pauses, false starts and frequent interruptions.” This surely illustrates how we have a bunch of activities that all have an ‘essence’ of wellness, but we do not quite know what that essence actually is!

Consistent with this, Medin and Ortony argue that we often do not have a fully worked out explanation of what the essence is that determines category membership. What we have is an ‘IOU for a theory’: a belief that there must be something that plays the role of essence, even though a description cannot be readily supplied. And so surely this is the case with wellness. We sense that we know what it is when we see it, but we cannot really pin down the ‘essence’ that binds these disparate activities together.

Wellness and cultural cognition

One way of understanding these intuitive decisions about the essence of categories such as ‘wellness’ is cultural cognition: the way cultural values shape our beliefs. To this end, we turn to the work of Dan Kahan who outlines the way cultural cognition explains why groups with different cultural outlooks (such as left or right of centre political orientation) disagree about important societal issues.

Clearly there is a huge array of cultural values we could choose from: what we are seeking in the context of wellness is those values that help to explain how such a diverse range of items could be included in this category. We could, for example, choose a cultural value such as ‘naturalness’ but this does not help us to determine why things as diverse as financial wellbeing and Reiki are both considered to be wellness solutions.

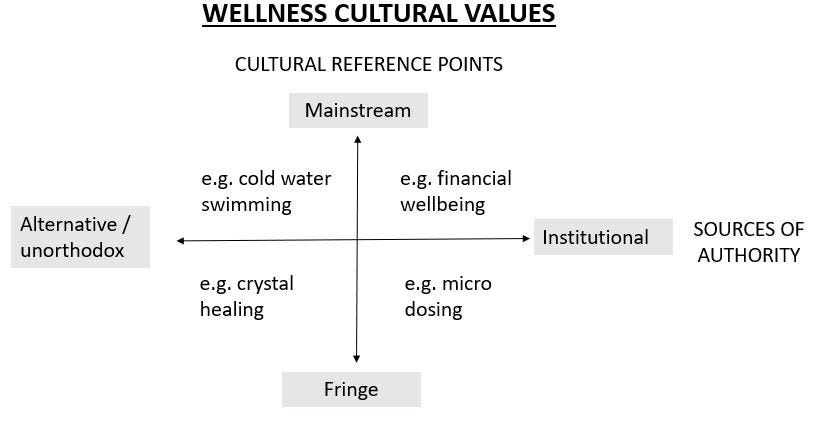

This huge variability in the topics in the category determines the cultural values we can draw on to look at this issue. We suggest two axes are useful here:

Cultural reference points: This is the way some people value ‘mainstream’ cultural references versus those that value more ‘fringe’ reference points.

Sources of authority: Some people value institutional sources of authority whilst others may look for authority from alternative, unorthodox sources.

For illustration purposes, we can see how this applies to a range of disparate wellness activities. For example, cold-water swimming is supported by evidence that is debateable, but largely considered to sit in mainstream cultural reference points. By contrast, other activities such as those we saw relating to the use of crystals for wellness arguably lack an evidence base of effectiveness beyond a placebo effect and we might consider they tend to appeal to people that typically have more fringe cultural reference points.

Similarly, a focus on topics such as financial wellbeing are often the focus for those people that value both mainstream cultural references and the role of institutions to validate the claims made. And finally, activities such as micro-dosing are in focus for those that value activities that are worthy of exploration by science- based authorities but that, nevertheless, draw on fairly fringe cultural references.

It is important to note that these categorisations are for the purposes of illustration and hypothesis generation –primary research is needed to validate and flesh them out. But hopefully they show the way we can see the way in which these cultural values shape the way in which people can have quite different ways in which they understand wellness – whilst at the same time all these different activities continue to fall into the category.

This is not a static picture: for example, yoga has arguably moved from a position in which people that preferred fringe cultural references and relied on unorthodox sources for to assess veracity of the claims have now moved to a position which appeals to those that value mainstream cultural references and institutional sources of evidence. But in that process, we can expect the original proponents of yoga may feel that this transition (and the inevitable change in the way it is practiced) has resulted in an inauthentic variant of the discipline (in the way it is practices and positioned) which no longer appeals to them.

With this in mind, we can see how some groups consider they are effectively excluded from some versions of wellness. This is the perspective of Fariha Róisín who sets out the way that wellness culture has become a luxury good that excludes Black, brown, and Indigenous people.

We can also see the way that some wellness practices are driven in part by the ‘Underdog effect’, as those holding minority beliefs and challenging widely accepted scientific perspectives can feel as if their perspectives are being closed down by authorities. Given this, it is not difficult to see how conspiracy theory provides a common language, bringing these beliefs together as there is an embrace of stigmatized, or rejected knowledge. This is increasingly explored in the issue of Conspirituality, which seeks to explore a ‘rapidly growing web movement expressing an ideology fuelled by political disillusionment and the popularity of alternative worldviews’.

In conclusion

Given the huge theoretical and practitioner base concerning wellness activities, it might seem strange to suggest there is a lack of fixed share meaning. But what theorists understand versus the wider public can of course be very different.

Across the wider public there is a case to be made that the logic that links together the different items the category is elusive. Many items are placed into the category of wellness, but the lack of a shared, fixed meaning can lead to intuitive definitions, shaped by very different (and likely unexamined) cultural values that we hold.

Should we be concerned? There is, after all, a raft of things that we need for our wellness and different things will work for different people. But perhaps without some clearer shared meanings of what wellness involves, then we also run into dangers: some groups can be excluded from certain activities as it seems that certain wellness behaviours are tacitly only approved for specific groups of people. But also some may find it a surprise that although the way while they define wellness in a very mainstream way, it also sits in the same category as practices which are very fringe. Nothing wring with that necessarily but perhaps not always what is expected by people offering these services.

A more explicitly multi-dimensional understanding of wellness is perhaps called for which does not rely on intuitive cultural nuances: given the grouping is used then we might infer that there is an underlying essence that has a logic for people. But perhaps more clearly identifying different orientations to this diverse discipline that reflects the key cultural values that shape the way people understand it, could well be a helpful approach.