Why change does not happen if we are just not feeling it

Recent research suggests we can better understand why people fail to adopt new technology by looking at the emotions involved

A recent article in The Atlantic magazine highlights the somewhat baffling contradiction of the microwave cooker – although you can find many beautifully designed and technologically advanced cookers, coffee machines and bread makers, the microwave device, the report suggests, ‘has responded with a resigned shrug’.

What, we might ask, is the reason for such apparently poor adoption of technology in this area? While there is a range of possible issues, one area that merits a closer look is emotion. The ‘resigned shrug’ means this may seem like a bold claim but this apparent lack of emotion may itself be an issue. In fact, recent papers by Carmen Valor and colleagues (see this paper and this paper) suggests we need to look closer at the importance of emotional response as a driver of innovation adoption.

The story of microwave innovation

Countertop versions of the microwave appeared in the 1960’s ushering an era of frozen dinners that could be quickly cooked. Since then, it seems the only real advance came in the 1980’s with the advent of the turntable which was included in pretty much every microwave. Otherwise, most of today’s microwaves work in the same way as the very early devices: reflecting microwaves around a cooking chamber which cause the molecules in the food to vibrate and heat up.

This is despite better methods of microwave heating long being available. For example, in 1988 Panasonic introduced inverter technology, allowing the microwave to cook more precisely at lower power levels and prevent overheating. Although many companies now sell inverter microwaves, the slightly higher price means that there is little take-up of these sorts of options. It seems, according to The Atlantic, that microwaves have been optimized not for performance but for price so that any innovation could seem pointless to consumers who appear to be expecting the bare minimum. But can emotion also be playing a part here in reducing propensity to spend money for new technology adoption?

Emotion has been overlooked as a driver of adoption

Valor argues that the role of emotion in take-up of innovation has not always been explored in detail. Instead the focus has been on seemingly cognitive motives of innovation adoption, with the four dominant theories in this area being innovation diffusion theory, the theory of planned behaviour, the technology acceptance model and the unified theory of acceptance of technology. Valor suggests that all of these downplay the role of emotion.

However, as we know from our own experience, adoption comes not only from what we think of innovations but also by how we feel about them. Indeed there is no shortage of research that confirms emotions are fundamental to decision-making, consumer behaviour and social change . We also know that emotions are key to shaping perceptions of risk , which is frequently important in decisions about taking up new technology.

Furthermore, given innovation adoption usually involves some degree of effortful choice, then emotions can provide the ‘motivational energy’ needed to overcome the inevitable barriers to adoption. Added to this, emotions underpin interpersonal communication and social dynamics and, as they are observed by and shared with others, they can shape the diffusion of innovations. On this basis, Valor suggests that the social expression of emotions is critical for the wider acceptance (or rejection) of innovations.

Emotion & cognition are not mutually exclusive

When unpacking the role of emotion there is often an implication that it is something different to cognition. But there is in fact a great deal of research showing that emotions operate in tandem with cognition to shape our choices. Rather than being two independent systems, evidence points to them being ‘systematically intertwined’ and influencing each other. This means that when designing strategies to promote the uptake of innovations, research on the cognitive influences of innovation needs to be integrated alongside the role of emotions.

So how does this work? Valor suggests that emotions have been considered primarily as a means of innovation evaluation (in terms of approach / avoid) with emotions such as enjoyment, fun and pleasure associated with favouring adoption and feelings of anxiety, concern, dislike or fear discourage adoption.

While this seems reasonable, simply aggregating emotion in this way so we look at valence (positive or negative) means we can fail to understand the more nuanced role that emotion can play. A recent paper by Ipsos has highlighted the way in which emotion can in fact be conceptualised by a number of components:

Valence, showing whether an emotional response is positive or negative

Arousal, defining the intensity of an emotional response

Control, revealing the degree of influence a person feels they possess in a situation

This suggests that emotion can be looked at in a much more nuanced way than the somewhat binary approach / avoid perspective.

What emotional responses can tell us - self-conscious emotions

On this basis, we can see that emotions provide us with a great deal of information about how people are feeling about innovation adoption. A good example of this is self-conscious emotion. To explain, innovation adoption is often driven by the fit with consumers’ desired social-identity which points to the importance of self-conscious emotions (such as pride, guilt and shame). These are so called as they need some awareness of the self on the one hand and group norms on the other, meaning that self-conscious emotions require the capacity to evaluate one’s self in the light of others. Self-emotions signal the fit or otherwise (of the innovation) with the consumer’s desired identity.

There are relatively few studies examining the influence of these self-conscious emotions on intentions to adopt but one example is a paper looking at the use of doggy bags as a potential solution to food waste. The study found that people report anticipated guilt for not asking for a doggy bag, on the basis that such an action would be at odds with their personal moral norms. However, asking for the doggy bag also activates anticipated shame as doggy bags are often not socially acceptable in many contexts (e.g. in some countries, or types of food outlets). These conflicting self-conscious emotions are, the authors conclude, a major barrier to adopting this low tech and environmentally-friendly innovation.

In the context of microwaves, their long history may mean that they are associated in people’s minds with convenience cooking and as such we may feel shame if it was to be revealed to our dinner guests that we had used one to prepare the meal. On the other hand we may feel pride about the use of such an energy efficient option and, in some circles at least, for the boldness of using the little known innovative aspects of some microwaves.

Understanding the mix of emotions might be key for innovation adoption

We can therefore start to see that we have a huge range of sophisticated emotions concerning innovation adoption. We might assume that mixed emotions might inevitably lead to low propensity to adopt but in fact Valor suggests things are more interesting than that. Blends of emotion will influence innovation adoption in different ways and at times will in fact increase adoption: for instance, high anxiety increases take-up when consumers also experience a great deal of hope about the prospect of positive outcomes from the innovation. This could be due to both hope and anxiety being future-orientated and goal-focused emotions, so they can help us to see how the innovation can help achieve personal goals.

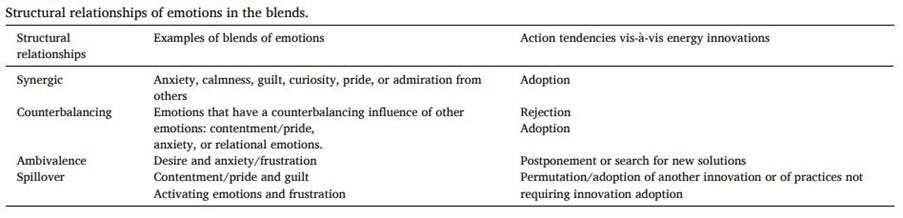

The way different emotion blends can operate is set out below – and, while based on qualitative work, it offers some useful starting points for practitioners:

This begs the question of what blends might be relevant in the context of microwave innovation adoption? Following this paper, if we buy a new microwave with advanced features we may feel anxious that it is expensive and could be difficult to use, angry if the tutorial fails to explain how to use the gadget effectively but we can also be hopeful or even joyful about the leads we could produce with it. Helping people to manage these emotional responses in a way that will result in adoption rather than rejection could well become a key element of marketing and customer services skills moving forwards.

In conclusion

Some of the ways in which emotion is discussed within behavioural science has tended to give it an important yet constrained role as being an ‘irrational’, automatic response to stimuli. But the research literature has long suggested a much more nuanced story – the work of Valor offers some very helpful guidance on ways in which we can better understand this. By deconstructing emotion we have at our disposal a means to consider more carefully the way to understand and help to guide innovation adoption. And this is right the way through the adoption process of course, from awareness and contemplation to continued use and even replacement.

There are also wider reasons why we might want to have a more nuanced understanding of emotion: sociologist William Davies has set out the way that emotions are often the principal way the world is shaped today, replacing the role historically given to reason. Of course, that emotion can be a powerful tool for mobilisation is not new but he argues it is more important than ever and is at the heart of much political rhetoric (such as the Brexit debate). Perhaps the collective nature of emotion also means it can create the opportunity for widespread change for a wide range of societal challenges in a way that might otherwise be slower coming.

It seems that the humble microwave and our feelings associated with our apparent reluctance to adopt new technology may offer us a lesson that tells us something much wider about ways in which we can encourage change.