From belief to faith

There is much to learn from faith-based communities about the way we understand belief

For a word that is frequently used but often unexamined, ‘belief’ shapes an awful lot of today’s debates and discourse: we live in a world where there often seems to be astonishment about the beliefs other people hold. Indeed, beliefs sit at the heart of much discussion about societal challenges such as mis / disinformation and culture wars and is also increasingly it is at the heart of how people make consumer choices.

No wonder then that this has become a topic that grips us – what we believe, how strongly we hang onto those beliefs, and how people might be persuaded to consider different beliefs is very much on the agenda for both policy makers and marketers.

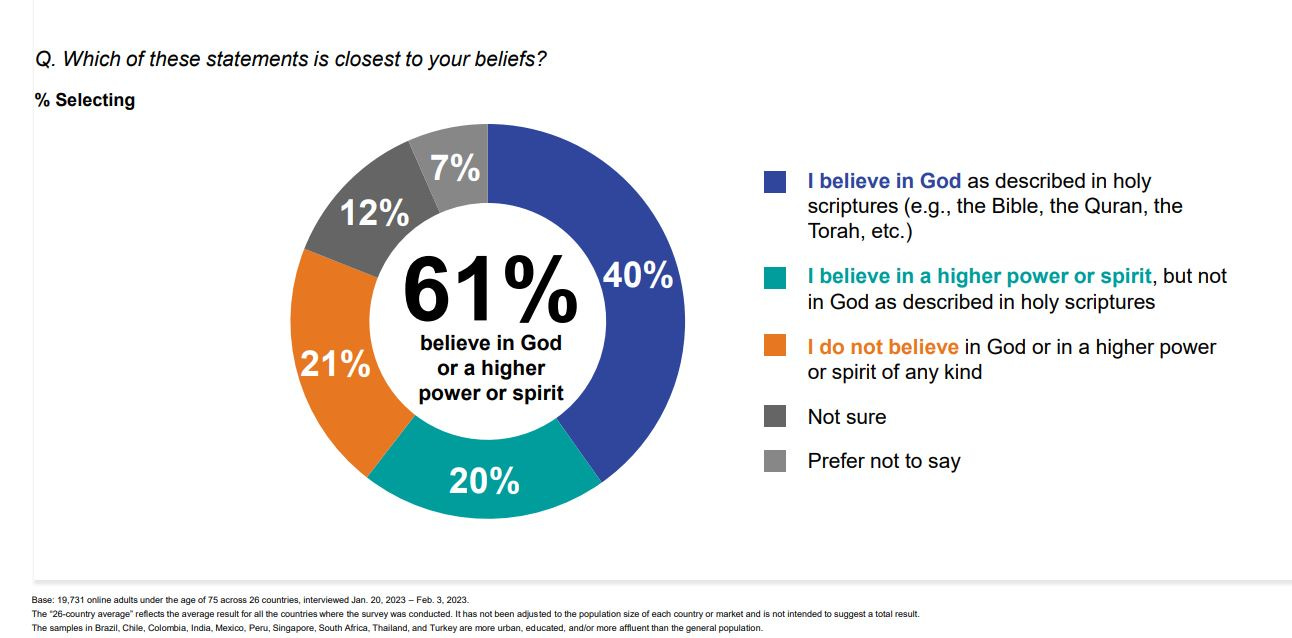

But just how good are we at unpicking what a belief actually is? Given its importance it seems sensible that we should cast a critical ‘behavioural’ eye over this term. To help us with this we will look at religious beliefs: this is a particularly interesting area in which to study belief, as we live in world where those that believe in God or a higher power or spirit are now globally in the majority, as revealed by a recent Ipsos study.

Some might be surprised by such a high percentage holding religious beliefs given this requires people to adopt a position that can seem at odds with the world as we know it. But perhaps this makes it the ideal subject to explore belief - how people hold religious beliefs in such an apparently non-secular and material world seems an important avenue of enquiry.

To help us, we have chosen a study on evangelical Christian belief undertaken by anthropologist T.M. Luhrmann. She makes a compelling case for how it may be faith rather than belief that helps us to understand evangelical Christianity and we suggest this offers a helpful way to understand the views of others more generally.

Discernment

In her well researched and respectful study, Luhrmann sets out the way we are generally aware of the difference between mental events generated in the mind (thoughts) and those generated from an external sources (perception). But in evangelical Christianity you are asked to consider some of our inner thoughts to, in fact, be perceptions of God participating in our private minds.

She uses the term ‘discernment’ to describe the cognitive and interpretive process by which believers learn to distinguish between their own inner thoughts and what they perceive as direct communications or signs from God. In the evangelical world, prayer is at the heart of this but also the ability to interpret patterns and apparent coincidences as signs from God.

This requires the development of what Luhrmann calls ‘noetic’ knowledge, a type of experiential understanding that is deeper than the everyday. This sort of knowing is described as being a little like wine tasting: it is only with practice that you learn to distinguish the subtle differences in the taste of different grapes, and develop your own discrimination system.

Managing disbelief

But of course we live in a world where the notion of God talking directly to a congregant is out of step with the way we are taught to understand reality. As Luhrmann says:

“The experience is inherently ambiguous, and the sceptic’s temptation is to dismiss the experience as so much human gunk.”

So just how are Christians able to hold onto their beliefs despite the scepticism that they encounter time and again? This is a profoundly social process that is recognised by religious institutions: there is a great deal of collective work involved not only to teach people to develop these apparently private and personal relationships with God and to help someone to stick it out in the face of their inevitable doubt.

In a recent interview Luhrmann talks about the way prayer groups would pray over someone who felt inadequate and remind them about God’s unconditional love for them:

"People practice experiencing God as a therapist, they have a sense of God being wise and good and loving, and they talk to God in their minds and talk about their problems, and then they are seeking to experience themselves as seeing it from the perspective of a loving God who then reflects back on their anxieties and interprets them differently”

Hence, for those in faith communities Luhrmann suggests not only that there is an straddling of the line between the ‘real’ and the ‘spiritual’ but this takes work to maintain.

Managing cognitive dissonance

The holding of two or more contradictory beliefs, values, or attitudes and the mental discomfort that follows from this is something that is tackled by the theory of Cognitive Dissonance. This suggests that people are motivated to reduce this resulting discomfort, typically by changing their beliefs or acquiring new information that supports their existing beliefs.

Luhrmann’s research suggests something different for faith communities who work to side step this: she suggests congregants learn to live with both the spiritual and material worlds, even when they may seem contradictory. She uses the concept of ‘ontological shifting,’ to describe the way people in faith communities move as needed between these different frames or realities to maintain a coherent worldview. Added to this, there is a tolerance of paradox and uncertainty that comes from holding seemingly contradictory beliefs.

So rather than seeing contradictions as a problem to be resolved, people might instead see this as an inherent aspect of the divine mystery, thus reducing feelings of dissonance. This suggests there is a dynamic and evolving process of understanding of the world that takes places rather than something fixed and binary.

Given the Ipsos findings that 40% say they believe in God (as described in holy scriptures) and 20% believe in some other form of ‘higher spirit’, then it is clearly not uncommon for people to straddle this line between the ‘real’ and the "spiritual’.

From belief to faith

Against this backdrop, philosopher Wilfred Cantwell Smith argues that religious faith goes beyond an intellectual assent to a set of beliefs (which are considered as something broadly optional and voluntarily embraced). He proposes that faith is a better way of describing the complex and dynamic components of religious engagement. While beliefs may provide an underlying structure or framework, faith can be thought of as a sense of trust and commitment to a larger reality, one that goes beyond intellectual understanding.

And this is not something that is settled on, but rather seems to be an active process. In the same interview Luhrmann talks about the way people use their imaginations to create an ongoing conversation to maintain their faith:

"They're using their own understanding of conversation — their own conversations and friends — and building this daydreamlike exchange, but they're seeking to represent God the way that God is represented in church…and then they're trying to experience that God as talking back to them and to experience what God says as being really real, and not the creation of their own imaginations."

Conclusions

On this basis, it is unlikely that people can be easily persuaded to change their world views simply by being presented with contrary evidence or arguments. From a faith perspective, truth is not merely a matter of fact-checking or empirical verification as it involves a meaning, and purpose that will often transcends empirical evidence. Indeed, the Ipsos research finds that 76% of those that believe in God or a higher power/spirit agree that “Believing in God or higher forces gives meaning to my life.”

Understanding different worldviews from this faith perspective allows us to consider the ‘ontological flexibility’ of people (in both secular and non-secular areas) where uncertainty, paradox and contradiction is an inherent and inevitable part of how they operate.

This may well offer ways to approach important societal issues such as dis / misinformation or culture wars where people seemingly struggle to take on board the counter points that are being made. A faith-based model of the views that people hold moves the conversation away from the individual and their possible shortcomings (e.g. their ‘crippled epistemology’ as Cass Sunstein called it) and to focus on the complexity of the subject matter.

The opportunity here is that we can find ways to engage and create connection with people that hold fundamentally different worldviews. This surely opens up new avenues for dialogue, understanding, and respect, helping us to navigate our pluralistic world with more empathy and compassion.