How experiential learning offers agility in an unstable world

Learning by doing rather than telling is not new: but this era of instability means we need to give it a renewed focus

Living in a particularly unstable and unpredictable period of history means we are more reliant than ever on learning anew: many of the things we know from the past will not necessarily serve us well, either now or in the future. This means we need to think more carefully about what learning in a ‘Liquid’ environment actually involves – as we are all familiar with the way that all too often just informing people about things does not work.

Instead, we make the case for encouraging learning that gives us agility, meaning we are better able to anticipate changes based on fast moving events, where we can adapt and change to tackle the problems before they become too large to overcome. At the heart of this we make the case for the way that experiential learning is key to supporting people to navigate the world in an agile way.

And while we may not always see the challenges as ‘learning’, much of them are in fact just that: if we are wanting to convince people of the value of something they are not currently doing, then this is a ‘learning’ question. We consider that policy makers and marketers frequently engage in ‘learning by telling’ (‘by doing this there are benefits to be gained’) rather than ‘learning by doing’ (‘when people do this, they typically realise the benefits.)

How we learn by experiencing

We start in a perhaps unexpected place – pillows. While most of us take it for granted that we sleep with a pillow at night, psychologist Itamar Simonson reported that he had happily slept without the aid of a pillow until mid-life and did not really see the need for one. However, when Simonson was in a store one day a promotional offer caused him to try one out and, to his surprise, he found he enjoyed the experience.

Simonson argues that much of the time we have stable explicit preferences that we are conscious of. But some of the time we also have preferences that we are not aware of, that only emerge upon experience. For example, we may not think all that much about financial planning and it is only when we start the process of this, perhaps with a financial advisor, that we become aware of what we consider to be important to us which in turn influences choices of pensions, savings and so on.

By resting his head on a pillow at night Simonson could start experience the feeling of softness, the levitation of his head, different sleeping positions and so on. It would be hard to anticipate whether you liked or disliked these if you had not experienced a pillow before.

Learning about the difficult stuff

One of the challenges here is that we may simply not want to engage on a topic and have a dialogue about the benefits and pitfalls. That is particularly the case for personal finance where the UK public have low levels of awareness, knowledge and skills. Findings from the Money and Pension Service suggest that:

Fifty-five per cent of working-age adults do not feel that they understand enough about pensions to make decisions about saving for retirement.

Forty-seven per cent do not feel confident making decisions about financial products and services.

We clearly have a problem- how do we get people to engage with these difficult topics which can feel daunting. Indeed, research by Simona Botti on making choices between what might be considered difficult alternatives, suggests that we are more likely to dislike making a decision and also be less satisfied with the outcome.

A series of papers known as the Competence Hypothesis indicate that if an individual is considering making a risky decision, they are more likely to take action if they feel knowledgeable in the domain, compared to not. For example, sports fans are more willing to bet on sports events compared to a chance event with similar odds. Psychologist Amos Tversky established that the primary reason for this is because knowledge affects perceived competence to make a decision. Hence, when individuals feel that the decision is in an area they are more familiar with, they feel more able to assess the risk, and are more likely to engage with making a decision.

Surely this is a case for experiential learning – simply telling people about financial products is less likely to land. Not only do not we not know what our preferences are, but we cannot start to determine what they are until we get started engaging in the challenge. But once people do, then experiential learning provides better outcomes. For example, individuals with credit cards are less likely to incur fees the longer they hold a credit card, as the regular credit card statements offers experiential opportunities for individuals to learn the needed financial behaviour.

A model of learning

This tells us something important about the relationship between thinking and doing. John Dewey noted this in the 1930’s, suggesting that while experience was important, it was how we reflect on and therefore learn from that experience that is critical.

This spawned a wide range of learning theories which have their strengths and weaknesses but one that is deserving of attention is from John Boyd: the reason this seems particularly pertinent now is because it gives importance to the role of change as a key driver of how we learn, a fitting backdrop to todays ‘Liquid’ environment where the challenge of managing change is a defining feature.

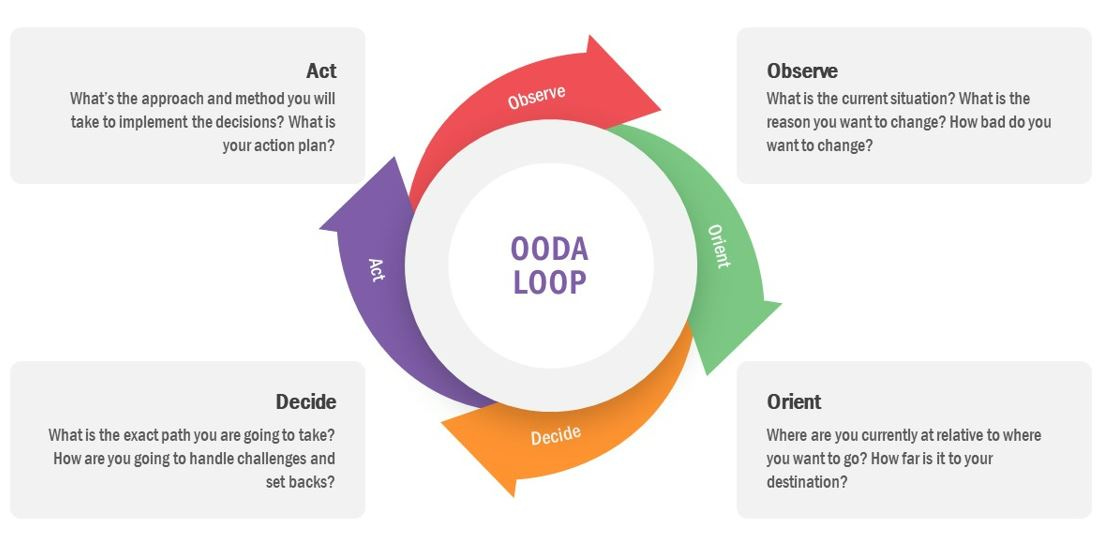

Boyd’s model is known as the OODA loop, involving four stages, all with feedback loops between them: Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. Observe is the act of filtering available information, Orientation is the point at which our mental models, our intuitive knowledge, are used to determine what we see and then provide intuitive guidance and control. This allows us to Decide which then leads to an Act, and influence events.

The notion of feedback is a key part of the model, recognising that we necessarily operate in a way that we do not have all the information available to us at any one time, so we need to make good enough decisions and then learn from experiences.

It is perhaps of little surprise that Boyd was a military strategist and used this approach to train soldiers to make time-sensitive decisions rapidly when there may not be time to gather all the information. The goal is not to be the best at each of the stages, but instead to go through the OODA loop process more quickly than an opponent. For Boyd, it is a ‘finger-tip feeling’ that determines success. It’s all about encouraging a way of thinking that is less about any kind of a rigid formula that simply gets executed at speed but rather it is about developing a means of informed intuitive action, understanding where that information comes from, and the impact that actions can have.

How experience is key to this

Linking this back to pillows, we can see that it was only when Simonson experienced using a pillow that he understood the value of a pillow in a way that was not possible before. People may have extolled the virtues of them for years, but the message did not land. Indeed, research shows we place greater weight on what we learn through experience and this is shown to lead to better calibration of expectations about the future.

Putting this in the context of the OODA loop, we can see that our Orientation (our mental models) might mean that we may fail to Observe the opportunities of a pillow, or indeed of a range of financial products and services that could well be of value to us. As such, it is therefore critical to find ways to understand the Orientation of people so that we can find ways to effectively engage them. We have previously talked about the way this we may need to create some disfluency, disrupting peoples intuitive dismissal or lack of attention so that we can then draw them into a conversation, and indeed, this type of OODA loop.

How do we apply this?

There are a number of implications of this for marketers and policy makers.

First, we are asking people to make more complex decisions than ever about a wide range of topics: with personal finance we are expecting people to be able to make investment and savings decisions and even the most sophisticated of us seem to be able to make careless errors. And this can also be applied to purchase decisions – how we make sustainable choices or engage in decisions about which type of cheeses to buy for a cheese board for a dinner party can mean a wide array of information we need to orient ourselves towards.

Second, the environment we are in is changeable, things are much less stable and predictable than they once were, so we need agility to be able to embrace this change and adapt to unfolding circumstances – whether this is a change of the economy, environmental priorities or new products becoming available and fashions emerging (e.g. what sorts of cheeses people are enthusing about.)

A traditional marketing or policy approach might be to inform us of the attractiveness and potential rewards that lie in wait if we decide a particular route – save for a pension with the upside of peace of mind, buy this sustainable item for a ‘warm glow’, buy this cheese to enjoy the perfect cheeseboard. But this can miss how these are things which we do not always know or fully appreciate until we start to engage more fully. And indeed, what we want may change as we then get more engaged but also as the environment changes.

An agile learning approach would focus much more on ways to bring people into a learning relationship, understanding their orientation and then shaping materials so they can Observe them in a meaningful way. This requires us to spark curiosity or challenge the way they are currently operating to pull them into a conversation. And once there is engagement, then offering a range of low-risk decisions allows people to Decide and Act creating feedback loops. Partnering in this way then allows policy makers and marketers to offer ‘scaffolding’ to support the way to think and act in these spaces – so that we are able to engage in an ongoing active and meaningful way.

This points to developing ways in which to build these ongoing forms of learning environments that support this style of engagement – for online marketers this will be engaging forms of customer experience that perhaps allows people to explore and engage with others; for financial advisors this is perhaps about supporting people in a way that allows them to think through their longer term needs in a more experiential way but also ensuring that there are opportunities to learn from actions in a more ongoing way. We can develop their intuitive Orientation to help people apply with their financial management, imbuing meanings beyond the numeric figures.

There are also opportunities for social causes – one interesting example being the use of virtual and augmented reality to re-create common experiences of marginalized groups. VR simulations show people what it's like to be homeless, pregnant, in a wheelchair, autistic, or a different ethnicity. The experiential learning of having to "to walk a mile in someone else's shoes" offers exactly the type of experiential, agile learning that is set out here.

We consider there is a case for reframing the way we approach learning – and indeed it is critical if we are to be able to find ways to support the population in the complex and changeable world that we live in.