What bullshit tells us about how humans communicate

It is often suggested bullshit shows our human susceptibilities but we can also see it as a conversational device with surprisingly positive purposes

It is said that truth is a fragile commodity as people readily talk ‘bullshit’ with no effort made to check the truthfulness or otherwise of what is said said to their audience, who in turn are duped into believing it. While this may at times be true, we will set out how bullshit can be more nuanced than this suggests, with all parties tacitly agreeing to a set of ‘bullshit rituals’ to oil the wheels of social convention.

This is important for us to understand given the problematic role bullshit seems to have in our lives. For example, Donald Trump is famously reported to have made 1,318 false statements in the first nine months of his Presidency. But in addition to making clearly false statements, he is also cited as a bullshitter for the way it appears he did not care about being truthful. For example, during his campaign, he stated that millions of illegal immigrants would be deported once he was elected which is given as an example of bullshit because Trump could not have been certain that, as President, he would have the actual authority to decide on deportations.

Another example which may potentially be placed in the category of bullshitting is the significant number of products being marketed as 'green', including up to 91% of all dishwashing items and 100% of toilet products. The Chief Executive of the CMA has indicated that the CMA is "concerned many shoppers are being misled and potentially even paying a premium for products that aren’t what they seem". It is therefore investigating the extent to which the claims can be substantiated – the claims made on behalf of these products may be revealed to be a case of bullshitting.

For something that seems so problematic, why does it so apparently widespread? To help understand this we used a behavioural science lens to unearth a surprising range of research findings. But we start our journey with on of the defining voices of this topic, philosopher Harry Frankfurt and his book On Bullshit.

What is bullshit?

Frankfurt makes a distinction between lies and bullshit: both the liar and the bullshitter try and get away with something; while lying is a deliberate act of deceit, bullshitting is when we offer up claims and information and we are simply indifferent to the truth. This ‘indifference to how things really are’ has therefore been at the heart of how bullshit is defined (and makes it distinct from lying).

With this in mind, one of the jobs that psychologists have been doing is to try and understand the audience - why do some people seem more susceptible than others and can we identify some consistent individual differences in bullshit receptivity?

Pseudo-profound bullshit

To explore ‘bullshit receptivity’, Gordon Pennycook and colleagues undertook research on what they called Pseudo Profound Bullshit. This is when “seemingly impressive assertions that are presented as true and meaningful but are actually vacuous.”

In a series of experiments, participants were presented with bullshit statements composed of buzzwords randomly organised in a way that provided syntactical logic but had no obvious meaning: for example, ‘Wholeness quiets infinite phenomena’.

The experiments identified that those more likely be receptive to bullshit are less reflective, lower in cognitive ability, and more prone to ontological confusions. They are also more likely than average to have paranormal beliefs and to support complementary and alternative medicines. Hence there are consistent cognitive styles that shape individual differences in bullshit receptivity which Pennycook suggests can be measured and understood.

Importantly Pennycook does suggest we need to take care before dismissing the capabilities of some people. It may be that the experiment participants assumed any statements that is part of an experimental study would be designed with some kind of meaning in mind. So the context might suggest a degree of meaning which might lead to them not being dismissed as readily as we would do in other contexts - we will come back to this point.

Seductive allure

To examine further if how the way information is presented can influence our receptivity to bullshit, Jonathan Silas and colleagues explored how people engage with explanatory scientific information. Specifically they assessed whether reductive or technical language (explanations that refer to more fundamental processes or smaller processes but do not offer explanatory information) obfuscates understanding: what is commonly referred to as seductive allure (in other words bullshit).

The study explored this in the context of behavioural intentions to take up a COVID-19 vaccine (this was in 2021 when COVID-19 vaccinations had been approved for use in numerous countries and had been shown to be safe and effective but yet been fully rolled out). They showed that when the participants were presented with good explanations, the introduction of additional technical language (bullshit) resulted in lower levels of agreement and propensity to take-up the vaccine.

This seems positive, suggesting people have a sense that the presence of bullshit means we should proceed with caution. There was, however, also a finding that people gave a better evaluation of poor explanations when they were accompanied by technical (bullshit) language - which influenced their stated likelihood to get vaccinated. So, it seems there is an allure associated with technical language in some contexts, offering evidence of the way bullshit can influence our behaviours.

Maybe then we are all vulnerable to bullshit – albeit for some people and contexts more than others. If so, this tells us something important about how our minds work – perhaps we often have a pretty hazy grasp of the world meaning we can be seduced by bullshit more readily than we think?

Are we all hanging on by our fingertips?

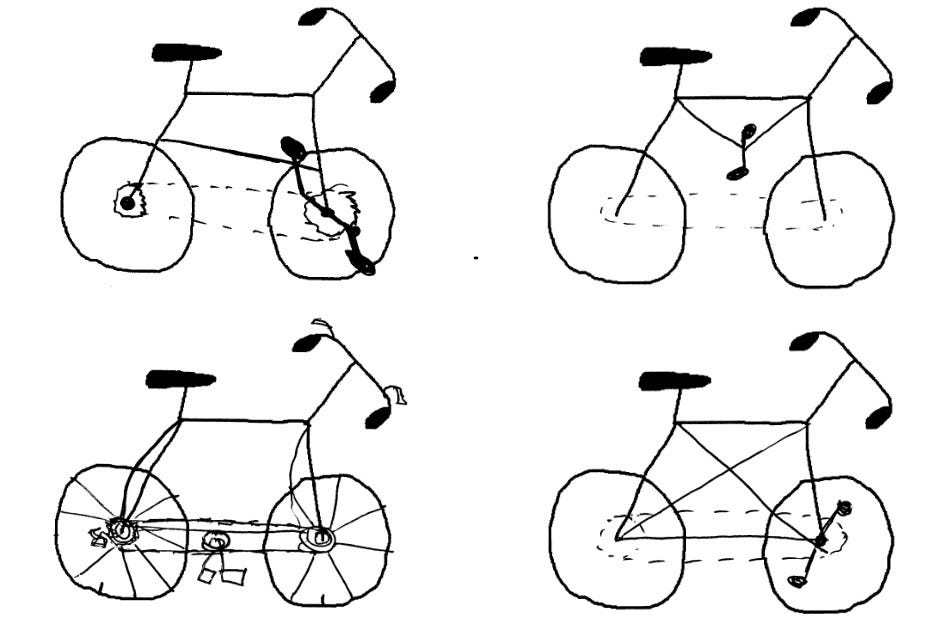

Research supporting the notion that we have a tenuous grasp on the world (and with that a receptivity to bullshit) comes from research by Rebecca Lawson who showed a group of psychology undergraduates a schematic drawing of a bicycle that was missing several parts. She asked the students to fill in the missing parts of the frame, the pedals and the chain:

She found that despite their claims of familiarity with how bicycles work, about half the students were unable to complete the drawings correctly – some examples of how they completed them are shown below:

So it seems we can often be in a position where we simply do not know the details of the very things that we are tasked with understanding, but all the time assuming that we do in fact understand it.

Building on this, Nick Chater's book ‘The mind is flat’, sets out the way we assume we have a great deal of deep thoughts but in fact, he claims, there is an abundance of evidence to suggest we make things up all the time. We come to conclusions on the fly and by confabulating explanations, with a mere illusion that we have understanding. If this is the case, it seems that we are hard-wired to be susceptible to bullshit.

This is congruent with a recent report on the BBC's reporting of economics which suggested that although there was "plenty to applaud" in the coverage, many journalists also ‘lack understanding of basic economics’ – so if even experts tasked with reporting on a technical subject seem to be bullshitting then what hope do we have?

Office bullshit

With this evidence, we might conclude bullshit reflects a deficit in human capabilities and that we need support to be more aware of our failings and take action to become more ‘bullshit literate’.

A counterpoint to this ‘deficit model’ is deftly provided by Dan Kärreman and Andreas Rasche of Copenhagen Business School who looked at what some might consider to be the epicentre of bullshit, the office. Offices it seems are a fertile ground for exploring bullshit as there is a tendency for what they call ‘unclarifiable clarity’ - language that seems clear but on closer inspection is meaningless. We will let readers be the judge of this but a recent finding that only 57% of UK workers understand their employer’s strategy might be read as supporting this!

So what can we pick out from the Kärreman and Rasche paper to help us understand bullshit? There are two points which stand out for us:

First, much of the analysis of bullshit seems to imply a straightforward notion of truth that ignores the way in which truth is not as straight forward as it might first seem - so what constitutes bullshit is contested.

“Our collective beliefs about what is true – about the world, about how it works, about our place in it – are extremely diverse and often contradictory.”

Second, by focussing on bullshit as a harmful enterprise, we tend to downplay the value of bullshit language for lubricating social interactions and exploring new ways of self and reality (see this paper and this one).

This seems quite a counterintuitive perspective given the concerns we have over fake news and misinformation, agendas that bullshit is often swept up with. But Kärreman and Rasche make a good case for the helpful role that bullshit often has in the modern organisation. For example, it can validate managerial decisions and actions as well as impressing and seducing a diverse audience who might otherwise not be attentive.

They suggest, for example, that notions (they consider to be somewhat bullshit terms) such as ‘strategic philanthropy’ and ‘shared value’ have helpfully legitimized CSR activities to investors and made actions in support of responsible business practices appear rational to financial markets. Bullshit can also help to rationalise and legitimize management decisions such as describing unpopular programmes as ‘right sizing’ or ‘cutting edge’ to emphasise the benefits to the organisation.

In this way they suggest bullshit provides a workaround for managers to offer a sense of commanding without commands or directives which can be negatively received – it softens the mandates . In a similar way, strategizing involves articulating goals in an interesting and exciting way whilst not fully knowing what is going on (to their point - reality can be contested ground). In these cases, the bullshitting job is to instil confidence using ‘aspirational talk’.

Similarly, they note that recipients of bullshit can be perfectly aware of its use but may well decide to let it pass. In other words, people have a sense of when a situation calls for bullshit: returning to Pennycook’s earlier comment, people may be good at recognising when the social context means bullshit is acceptable (or that it has some degree of meaning and import).

In conclusion

The informal nature of the word bullshit has perhaps meant it has not always been given it as close a scrutiny as other terms (such as misinformation or fake news). And yet the concerns we have about our epistemic environment being corrupted means that it is now something that is being looked at with greater interest. Is bullshit a new sort of informational currency (or even a longstanding device that is now increasing in usage) and if so, is this something we should be alarmed about?

The focus given to the subject by social scientists does seem to infer that bullshit is a problem as it can deceive and mislead. But if we move our lens slightly and see it as a conversational device rather than purely as a means of imparting misleading knowledge then we can see it opens up a range of new, more positive interpretations. And it can be all to easy to assume recipients are helpless victims when in fact we intuitively recognise the role it plays in managing social meaning and interactions.

There is a danger of taking a narrow ‘information-sharing’ lens to communication which might not take into account the wider social purposes of bullshit. We all use a wide range of unwritten speech norms when in conversation so meaning is imparted not only with what is said but what is implied. When we speak, we communicate meaning in two ways: conventionally – the words themselves and conversationally – the use of words in a specific context. For us to untangle things it requires both the speaker and the recipient to work together.

The interaction of these mean we are able to speak with nuance and subtly – some things are better left unsaid but inferred. And this is where bullshit comes in. It offers us a chance to float things, test stuff out, soften messages, inspire and suggest. That we have not made explicit lies but instead used bullshit means it is easier to deny, allowing for a ‘reactive reversal’ if what has been suggested does not sit well with the audience or our imaginative perspectives of the future turn out not to be true or practical after all.

In terms of the audience, the accounts of humans failings with regard to bullshit perhaps do not fully take into account what has been called the ‘paradox of the psychosocial’. This sets out how we might disapprovingly label people as suggestible if they accept knowledge from others as true despite lack of evidence but that it is this very capacity which is seen as something to be celebrated given it makes learning, affection, socialization and social cohesion possible.

Bullshit surfaces something about the nuanced nature of our relationship with information - we operate in a shared knowledge community where we rely on others making us vulnerable to ‘epistemic pollution’. But at the same time we understand that not everything that is said is necessarily all that is being communicated - we are collectively smarter than that.

On this basis we can make a case for a kinder view of bullshit, albeit recognising that it can be used for disreputable means as much as for positive outcomes.

Thanks to Professor Peter Ayton for a useful conversation when developing this article.

I suspect that one reason why 57% of UK employees do not understand their employer’s strategy is because 85% of corporate strategy is pseudo profound bullshit (btw, that stat is most certainly bullshit, but you get my point).