Fake it until you make it?

While it is fair to worry about the impact of fakes, we also have a much more interesting and engaged relationship with them than is often considered

We live, it can seem, in a world where we can no longer trust our senses, with ‘deep fakes’ renegotiating our relationship with reality. Take the below example of the AI-generated image apparently showing an explosion near the Pentagon – this sent ripples through the stock market before it was quickly realised the image was a fake.

In another recent example, a photo of the UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak appeared to show him pulling a sub-standard pint at a beer festival while a woman in the background looks on with a derisive expression. The image had been manipulated from an original photo (on the left) in which Sunak appears to have pulled a pub-level pint while the person behind him has a neutral expression. Again, this was quickly identified as a fake.

Are we fallible humans destined to be duped by increasingly sophisticated technology that means we can no longer separate fact from fiction, the authentic from the fake? The data certainly does not look great, with a number of studies suggesting that humans are not able to distinguish between real portraits and AI-synthesized faces.

Fakes are indeed seen as a problem, with the United Nations calling AI-generated media a “serious and urgent” threat to information integrity, particularly on social media. In a recent report, the U.N. claimed the risk of disinformation online has “intensified” and singled out deepfakes in particular.

Given what we know about human psychology, to what extent are in fact fakes renegotiating our relationship with reality? We suggest that while there clearly is a cause for concern, there is also a case for understanding better the way they also tell us something important about human perception.

This is potentially important for those engaged in behaviour change as, given they seem to challenge our notions of what is ‘real’, this potentially opens up a way of challenging peoples’ intuitive assumptions about the world and, with that, opening up possibilities of change.

The psychology of fakes

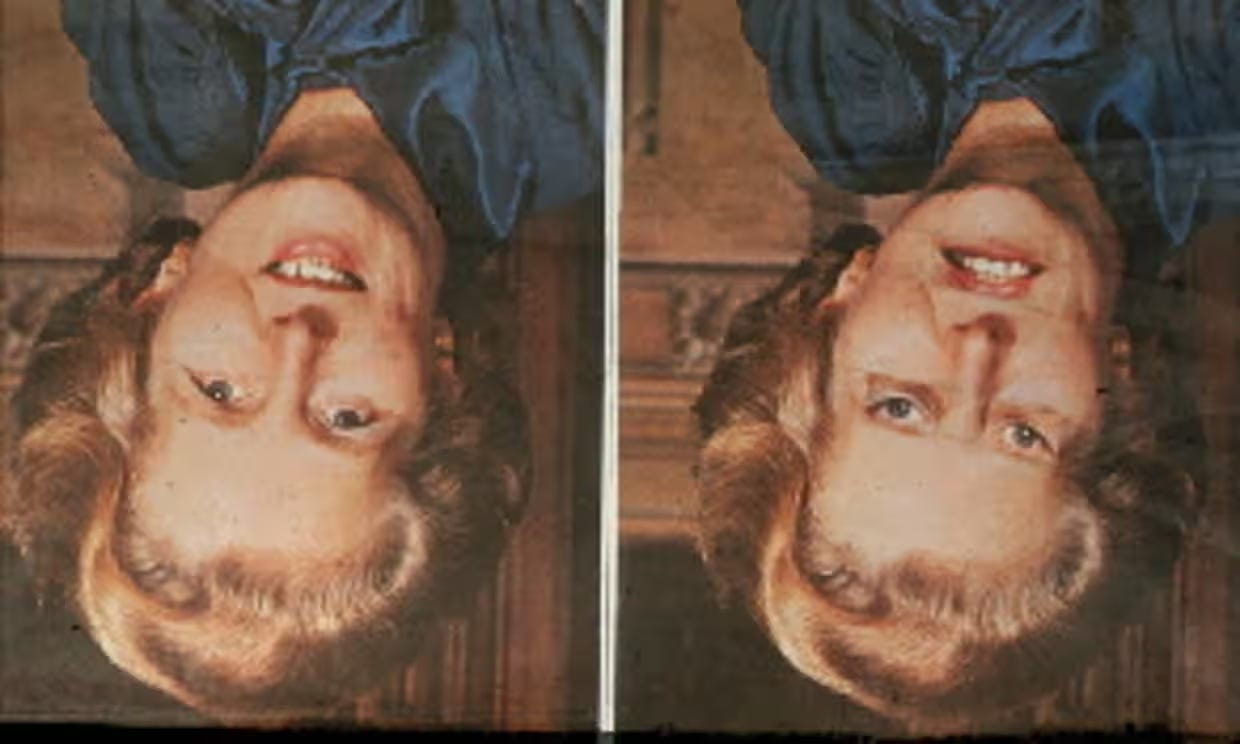

The psychology literature about fakes tends to suggest that our brains can’t process all the information we see at once, which is why we often take a long time with games like Spot the Difference, or are befuddled by optical puzzles like the “Thatcher Illusion,” a seemingly normal image where we can see something is wrong but find it hard to spot that it is due to the way Margaret Thatcher’s eyes and mouth are inverted.

Psychologist Dann Simons says that is because our brains fail to log details deemed unimportant. When we flip back and forth trying to find them, we can’t because we never noticed them in the first place.

This chimes with research on inattentional blindness. In their classic experiment, Simon and Chabris show the way in which a person in a gorilla suit walking in a film sequence can be missed because the participants in the study were ‘primed’ to count the number of basketballs passes. Daniel Kahneman uses this as an example of how we can be ‘blind to the obvious’.

On this basis the omens for humans do not look promising.

But what really is a fake?

But before we reach too gloomy a conclusion about humans and our deficiencies in spotting fakes, there is a definitional problem that needs addressing. When we consider something to be a fake then it infers we can make a distinction between the real and the false. But are things really that simple? In fact there are many cases where, on closer inspection, this seemingly simple distinction starts to crumble.

Take the topic of art – on the one hand a huge amount of money and resources are involved in establishing the authenticity of paintings, seeking confirmation that they were indeed created by the hand of the artist. But at the same time, some artists such as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst are open about the fact they have teams of people creating artworks for them. Despite the artists not creating the works themselves but commissioning other people (which in other circumstances might be considered to be inauthentic) – the prices they garner suggest that this is not in any way a problem.

And our brains can convince the body that a fake treatment is the real thing — the so-called placebo effect — and thus stimulate healing. Given that under the right conditions, a placebo can be just as effective as the ‘real’ treatments then can the fake really be a fake as we commonly understand it?

As social critic Rob Horning suggests, it seems that what is real and what is fake is not always a straightforward process, as he comments with regard to ‘fake news’:

“That phrase implies that there is news out there that is not fake, that is entirely real, that is totally accurate. But nothing is totally accurate; everything is an approximation, and how close or far it is from the “truth” depends on where you are looking from and what you need to hear.”

All of this suggests that the notion of fake versus authentic is not quite as binary as it first appears: and not only that, but as we shall now see, perhaps at times people are even drawn to fakes.

We just baddies that’s smart with our money

A recent report in the Financial Times suggests that the trend for “dupes” has boomed in clothes, accessories and footwear. Journalist Annachiara Biondi wrote about the way some young people are attracted to fake items, enjoying identities of people that are making a smart move:

“For most of them,…the real faux pas seems to be paying full price for authentic products when replicas, allegedly of comparable quality and at one-tenth of the cost, are just one click away.”

Similarly, cosmetic surgery used to be shrouded in secrecy, with the notion that we could pass off our enhanced looks as genuine. This has now changed with celebrities such as the Kardashians openly talking about the procedures they have, which means that for many people there is no longer any shame in owning up that how they look is ‘fake’.

And in case we thought our complex relationship with fakes is recent, we can turn to Medieval history and the way people were drawn to religious relics. This is the practice of preserving and enshrining the remains of saints and heroes, or other items associated with their life or death. While today we perhaps might want some evidence of the authenticity of the relic, historians suggest that a Medieval person may well not have been that bothered by it being a ‘fake’ — as God was considered capable of imbuing anything with holiness. As art researcher Jennifer Freeman suggests:

“Relics… are shortcuts. They're visual mantras to focus the .. mind, a link between this world and the next.”

With all this we can see fakes are not necessarily always problematic for all concerned, what a fake is or is not can be contested, but also even items that are patently not ‘authentic’ can frequently be imbued with meaning and connection.

Back to memes

Our concern with fakes may distract us from what they offer those engaging with them – they help us to tell a story and a good example of this is the meme. A meme is typically not considered to be a factual document but instead is a rhetorical device. Rob Horning suggests that when something circulates within the context of ‘memes’, this specifies how it is supposed to consumed: as something made to mock somebody, make someone laugh, make a point and so on.

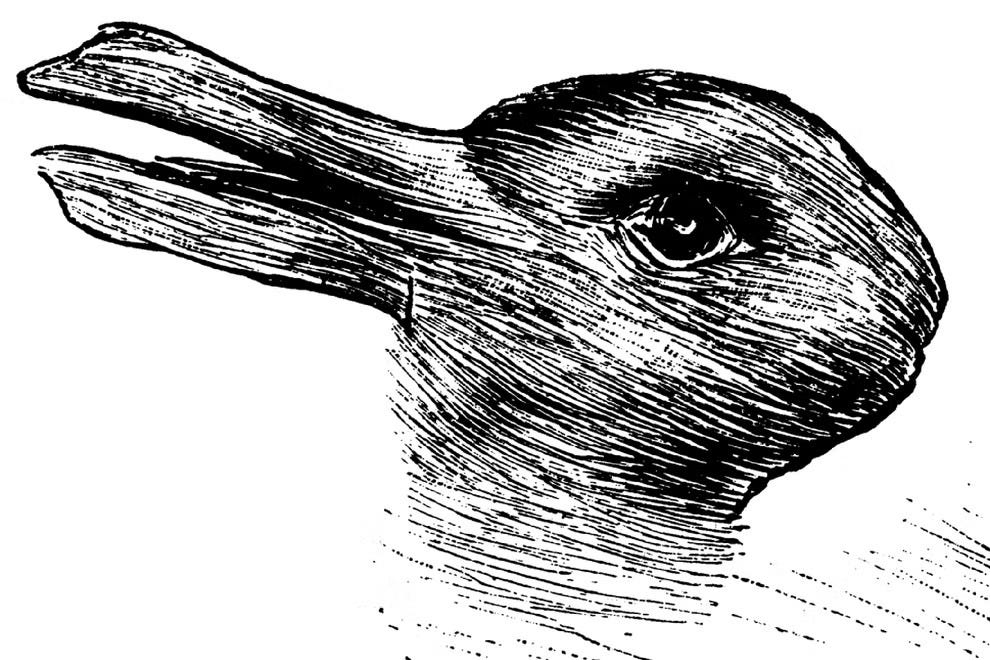

Horning suggests that in the same way as many visual illusions work, we often enjoy the sensation of being momentarily tricked, imagine others being tricked and maybe experience a ‘what if’ moment. Reality is momentarily suspended and what we took to be true, the world as predictable, stable and knowable, is one that has suddenly changed. This ‘liminality’ between what is real and what is not where our disbelief is suspended, is something that we are accustomed to also seeking from stories, books, and films.

There is something carnivalesque about it: in the same way, Medieval carnivals would mock the authorities at the time though ‘rituals of inversion”, with jesters or dancers costumed as priests and nuns. During Saturnalia, a Roman pagan festival, masters had to wait on their slaves; carnival allowed peasants to impersonate kings.

So fakes are not always strictly a means by which we separate fact from fiction but something we actively engage in, and work out how to understand about the world.

Buckets versus searchlights

We can see from the above that there are interesting psychological implications of fakes. A body of knowledge that seems relevant here is via psychologist Teppo Felin, who suggests that a ‘bucket theory’ of perception reflects the information we collect about our environment as passive and automatic. We assimilate a world that exists independent of ourselves, and our limitations means we can fail to spot fakes.

In contrast, a ‘searchlight theory’ of perception suggests that the way we make sense of the world is active, using guesses, theories, questions, and hypotheses, meaning that the way we comprehend things is by directing perception and attention. On this basis we do not always see fakes as we are looking in the wrong place, a type of misdirection perhaps.

Hence in the Simon and Chabris gorilla experiment referred to earlier, we could be asked to look at all manner of things from the hair colour of the actors to the gender and ethnic composition. Any of these are clear but only if you are looking for them and not something else. The fact that we miss something is not a function of blindness or bias, but an entirely rational and successful process given what we set out to do.

Arguably much of the narrative about fakes implies we use a ‘bucket’ theory of perception – hence the alarm that we are in danger of false representations of a solid, stable and one dimensional world. But as Horning suggests, perhaps fakes show that we have a more complex and at times playful relationship with the world. Hence a little like a visual illusion (which in a sense they often are) we switch between two different versions of reality; we can perhaps see that fakes might encourage us to understand that there is more than one way in which we can look at the world.

In other words, we are thrown into a moment where our understanding of reality is shaken up, and we can see other possibilities – our fast, intuitive processing slows down, fakes create ‘friction’ which means we are forced to stop and think, similar to the notion of ‘disfluency’ that we have noted previously.

In conclusion

There a danger of fetishizing the impact fakes on our lives and the danger this represents – as with any way in which we operate and communicate, they can be weaponised and used for nefarious ends. But at the same time fakes may not always deserve the degree of concern that often seems to accompany them. Indeed, we can all find examples of institutions and individuals that are not ‘fake’ but legitimate and authentic that have nevertheless wreaked havoc with people’s lives.

Fakes can be damaging that is clear but at the same time there is something interesting, subversive and challenging about them – they allow us to see reality in a different way, and for what we understand about the world to be reconsidered. This can create an interesting space to then disrupt the normal fluency of processing and reconsider the world as we know it. Which, for a behavioural scientist interested in making change happen, could well offer some untapped and useful opportunities.